Introduction: The everyday experience of uncertainty

Every weekday morning, commuters across Greater Kuala Lumpur (GKL) face a familiar predicament: Waiting under the equatorial heat, they open the MyRapid Pulse app to check when the next bus will arrive. The app displays that the bus is “8 minutes away”, but it remains frozen for several minutes, before disappearing entirely.

The commuter then receives a notification that there is an obstruction. By the time the delay is announced, it is too late for commuters to take an alternative route, or switch modes.

As one respondent explained:

“Walaupun kita tengok dekat apps kan, cakap ‘oh, [bas] nak sampai dah,’ walaupun [apps] cakap sampai pukul 12.30 p.m., tapi [bas] tak akan sampai 12.30 p.m,. [apps] cakap sampai 12.45 p.m.” (R21)

Others described the same uncertainty more bluntly:

“When the bus breaks down, at least they should inform the public. Otherwise, we have to wait for the bus to come.” (R25)

“So, 7.50 a.m. there is supposed to be a bus usually. And then the next will be 8.20 a.m. and so on right? But then, even though you come at 7.45 a.m., sometimes that 7.50 a.m. bus never comes until like 8.10 a.m. So then you’re left wondering, will the next bus come at 8.20 a.m. or would it come at a later time? There’s not really much information about that.” (R24)

Source: Shukri Mohamed Khairi and Gregory Ho Wai Son (2025)

These experiences point to a deeper problem than delays alone. They reflect a breakdown in informational reliability. Real-time information systems are intended to reduce uncertainty and help commuters plan their journeys. When these systems provide inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete information, uncertainty is not reduced but amplified. Commuters lose their ability to make informed decisions, manage their time or adjust their plans when disruptions do occur.

This loss of informational reliability matters because commuters evaluate public transport not only on travel time, but also on their tolerance for risk and uncertainty. Even when services are imperfect, reliable and timely information allows commuters to adapt. When both service performance and information provision fail simultaneously, the system loses credibility. Over time, this erodes trust and pushes commuters towards private vehicles.

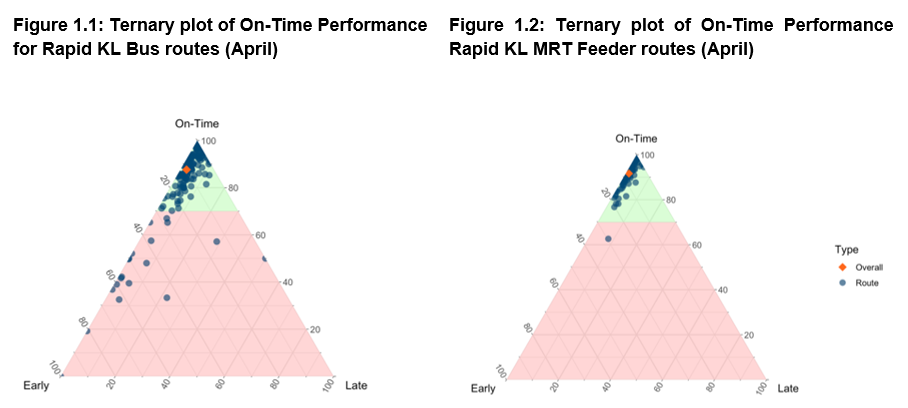

Evidence from Kelvin Ling Shyan Seng and Gregory Ho Wai Son (2025) reinforces this dynamic. Rapid KL bus services exhibit substantially wider variation in punctuality compared to MRT feeder services, with approximately one-fifth of routes collapsing into operational failure1 in a typical month.

For commuters at the bus stop, these performance patterns make dependable real-time information even more critical. When service frequency is high, commuters can often arrive at a stop without consulting real-time information. When services are infrequent or variable, however, the quality of information becomes the primary buffer against uncertainty, frustration, and eventual abandonment.

This policy brief argues that improving the delivery of real-time information is therefore not a cosmetic digital upgrade, but a core operational requirement for restoring trust in Greater KL’s bus system.

The current state of information systems

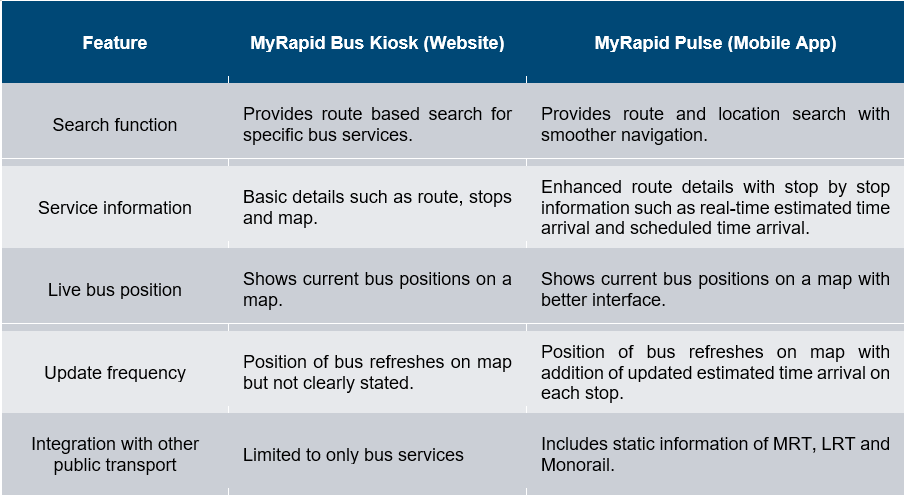

Rapid KL currently provides two official platforms for bus service information: MyRapid Bus Kiosk (website) and the MyRapid Pulse (mobile application). Both platforms offer basic route information and live bus location tracking. However, they differ in terms of functionality and commuter experience, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Official Rapid KL’s bus service information platforms.

Despite these features, the practical usefulness of both platforms remains limited from a commuter’s perspective. The core limitation is not the absence of data, but how information is structured and presented.

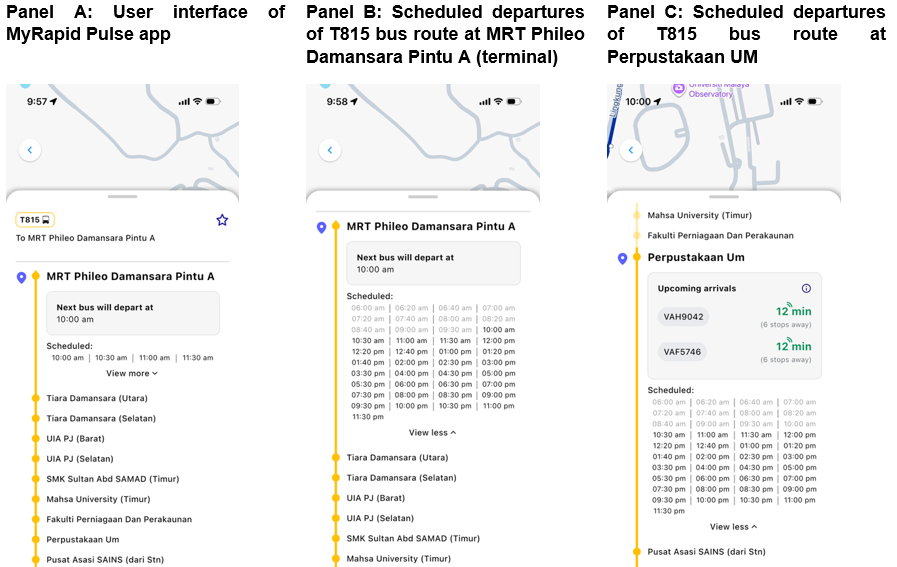

First, real-time information is oriented around vehicles and terminals, rather than the commuter’s stop of interest. While MyRapid Pulse displays the location of busses and their departure times from terminals, it does not provide scheduled arrival times at intermediate stops. A commuter checking the app from home or work, cannot reliably determine when a bus is expected to arrive at their stop without performing mental calculations and adding personal buffer time.

Second, the app displays ETA only for the immediate bus, without showing arrival times for subsequent services on the same route. This compresses the commuter’s decision horizon. Faced with a single uncertain ETA, commuters are forced either to rush to the stop prematurely, or to arrive much earlier than necessary. Both responses increase perceived waiting time and frustration, even when the actual delay is modest.

Third, the user interface obscures the distinction between scheduled arrival times and real-time estimates. In practice, what appears as a ‘schedule’ in the app often reflects departure times from terminals rather than expected arrival times at downstream stops. This can mislead users into believing that a bus will arrive at a specific time, when in fact no such stop-level schedule is displayed on the app.

From a systems perspective, this represents a missed opportunity. Historical and real-time GTFS data already contain the information needed to generate stop-level schedules and rolling ETAs that reflect observed operating conditions. Instead of being integrated into commuter-facing planning tools, this data remains underutilised, leaving schedules largely uninformative for everyday journey planning.

Qualitative interviews reinforce this diagnosis. Respondents consistently described the app as difficult to navigate and unreliable, particularly when disruptions occur:

“Sometimes [Pulse app’s] information is not up-to-date enough, because you need someone to report the issues to them, then they will update the app. The lack of real-time reporting.” (R7)

“Because I also downloaded the Pulse app, and I feel like the time is not always accurate.” (R13)

“They would show the location of the bus, but you would have to wait for a while to see which direction the bus is moving, whether towards or away from you. It's very hard to navigate.” (R20)

How to improve the delivery of real-time information:

Improving the delivery of real-time information does not require new infrastructure. It requires reorienting existing data and platforms around commuter decision needs. Three operational improvements stand out:

Provide stop-level scheduled arrival times alongside real-time ETAs of the next two busses

The most immediate improvement is to display scheduled arrival times at each bus stop, rather than departure times from terminals and one ETA. For commuters, the relevant question is not when the bus leaves its terminal, but when it is expected to arrive at their stop of interest.

Displaying stop-level scheduled arrival times, together with live ETAs of the next two busses, would allow commuters to:

• Plan departures from home or work more accurately

• Decide whether to wait for the next bus or adjust their travel plans

• Distinguish between routine delays and genuine service disruptions

This information already exists within the historical GTFS data. Integrating it into the MyRapid Pulse interface would therefore represent aggregation of already existing data, without requiring new data collection.

Revise scheduled headways using observed operating conditions

Note: Computed based on authors’ calculation.

Where routes consistently fail to meet their scheduled headways, scheduled should be recalibrated based on observed real-world performance. If a route rarely operates at a 20-minute interval, revising the schedule to a 30-minute interval with stricter adherence can improve reliability from the commuter’s perspective.

While this may reduce nominal frequency, it narrows the gap between expectation and reality. Evidence from the Kelvin Ling Shyan Seng and Gregory Ho Wai Son (2025) shows that variability, rather than delays alone, could be a key driver of commuter frustration. More predictable services, even if they are less frequent, can reduce stress and improve trust when paired with reliable information.

Importantly, schedule revision should be framed as an iterative process. As operating conditions improve, frequencies can always be adjusted upwards. The focus is expectation management that is aligned with operational capacity.

Introduce personalized, proactive information features

Currently, MyRapid Pulse functions primarily as a passive lookup tool. Allowing users to save preferred routes or stops and received targeted notifications would shift the platform toward proactive journey support. In this case, alerts for delays, breakdowns or cancellations can be pushed immediately to affected users in a more direct way.

Such features reduce the cognitive and coordination burden on commuters. When disruptions occur, frustration is driven less by the disruption itself, but more from the absence of timely information to help support commuters with making an alternate decision. Being informed early allows commuters to decide whether to continue waiting, reroute, switch modes, rather than being stranded at a stop with no guidance once a breakdown has already occurred.

Disseminate real-time information through multiple channels, including at high-ridership bus stops

At present, real-time bus information in Greater KL is largely confined to the MyRapid Pulse app. This limits accessibility for tourists, occasional users, and commuters who may not know which application to download or may not routinely rely on smartphones.

Integrating ETAs and disruption alerts into real-time arrival displays at selected high-ridership bus stops would ensure that these different groups of people still receive timely updates. Evidence from international studies show that visible, at-stop information reduces perceived waiting times, improves user satisfaction, and increases confidence in public transport systems.2,3,4Recent implementations by Transport for London (TFL) similarly highlight the role of on-site information in improving passenger experience5, particularly during service disruptions.

By making service information available both online and on-site, commuters gain greater certainty, a greater sense of control and reduced stress during their journey, even when services are disrupted.

Evidence from International implementations

Several large urban transport systems have implemented real-time commuter information reforms that directly address the problems identified in Greater KL. These reforms were operational changes that have improved perceptions of reliability, reduced passenger uncertainty, and increased confidence in bus services.

In Seoul, real-time bus arrival information is delivered both on-site and digitally. By 2025, more than 5800 bus information terminals have been installed citywide, providing passengers with real-time bus arrival information at stops6. At the same time, the mobile application provide similar information for commuter on the move7. The bus network are also supported by Seoul’s Transport Operation and Information Service (TOPIS), which integrates data from bus GPS, GTFS feeds and road traffic conditions8. TOPIS not only deliver real-time updates on bus arrivals but also issues alerts about disruptions, delay or breakdown.

In Denmark, the national journey-planning platform Rejseplanen, integrates scheduled and real-time information across modes, and it reinforced by real-time displays at major locations9,10. Commuters can access walk times, fares, transfer option, delays and service change through the app.

In Japan, many bus operators have adopted automated vehicle location systems linked to digital signage at stops and terminals. Digital signage at bus stop and terminal displays live arrival times, route details and service updates11,12. This helps passengers plan their journey confidently and reducing perceived waiting times.

Across these cases, the common outcome is not perfect punctuality, but improved predictability from the commuter’s perspective. By providing stop-level arrival times, timely disruption alerts, and information through multiple channels, these systems reduce uncertainty and strengthen trust even when service variability persists.