Introduction

The burden of care is a rising issue faced not just by Malaysia but also across the globe. The increase in dependant populations in tandem with a shrinking working age group has led countries to rethink how the former population is taken care of while still balancing economic growth.

This Regional Insights on the Care Economy series will outline how Malaysia’s peers are tackling the varying needs in their care economies. Specifically for this article, we will dive into aged care and how long-term care (LTC) is provided in Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam1. This will allow for a comparison with Malaysia’s own initiatives2.

The Burden of Care Varies Across Countries

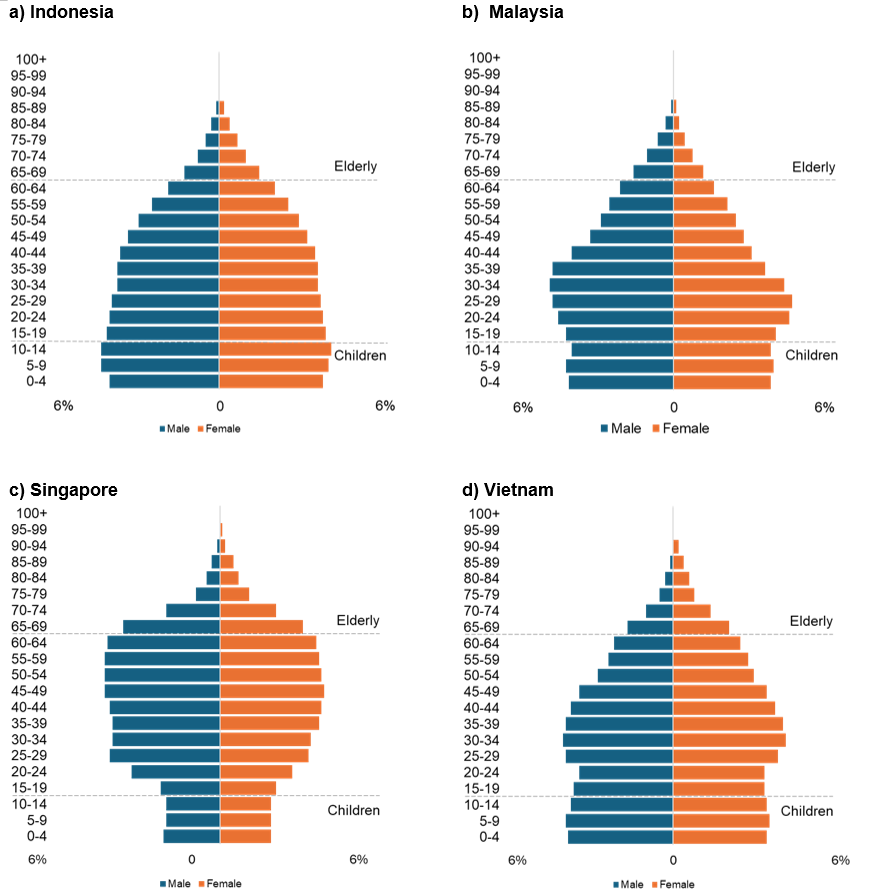

For context, an exploration of the burden of care across the countries of interest will first be provided. The care economy demands of a country generally depends on factors such as their income levels and differences in demographics. The population distribution of each country described in this paper is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 1: Population distribution by age, 2022

Note: The classification of children and elderly are based on UN and World Bank age groups that are typically used to calculate economic dependency. This dependency assumes that both children and elderly are economically non-productive and are thus dependent on working adults within the age of 15 and 64.

In terms of population, Indonesia is the largest of these countries with a population of 275,501,339 as at 2022, while Singapore is the smallest at 5,637,022 in the same year4. Indonesia’s (Figure 1a) population distribution has a pyramid shape, characteristic of a country with a still growing population. Majority of the population in Indonesia is of younger age, hence there is a greater need to direct care policies and funding to developing sustainable childcare infrastructure. Additionally, Indonesia, and similarly Vietnam is a country that faces the additional burden of exporting domestic workers, leading to an even greater need to expand long-term care (LTC) and childcare services relative to Malaysia and Singapore5.

Vietnam’s (Figure 1d) population pyramid features a more even distribution across age groups that indicates the demographic transition from a growing population to a stabilising one. However, on top of children already making up a large proportion of the population, their elderly population is also increasing at a high rate. Vietnam’s ageing speed6 was reported to be 27 years, with those aged 65 and above projected to make up 14% of their population in 20377.

Singapore’s (Figure 1c) population pyramid features a kite-shape, which indicates their rapidly aging society and declining birthrate. Both Singapore (20.7%) and Vietnam (13.31%) have higher elderly dependency ratios8 as they are rapidly aging and require urgent development on their LTC services. In comparison, Indonesia (10%) and Malaysia (11%) share lower elderly dependency ratios9.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia (Figure 1b) the younger half of the working age group still makes up the largest proportion of the population, with a fair proportion of the population being children as well. This suggests a need for sustainable childcare systems that can support workforce participation rates. However, this also indicates that within a few decades the elderly population will be rapidly increasing and Malaysia will also need to develop a strategy for expanding LTC.

Examining Aged Care

LTC in Southeast Asia is primarily taken on by informal caregivers, particularly female family members10. For our countries of interest, Singapore’s demand for LTC services currently appears more urgent than in Indonesia or Vietnam, with Singaporean adults providing 29 hours each week to care for elderly relatives on average11.

Unlike Indonesia and Vietnam which are large exporters of domestic workers, Singapore has a reliance on domestic workers for LTC work12. Indonesia and Vietnam also have a large proportion of their elderly population living in rural or remote areas and LTC services in these two countries have not yet expanded to serve most of these recipients13.

Although all three of these countries have a proportion of publicly funded LTC facilities, they are not universal in nature, primarily providing care for those with the most disadvantaged backgrounds. In Indonesia, means-testing is carried out to determine who is eligible for publicly funded LTC services. In a WHO evaluation in 2024, public LTC facilities in Indonesia catered to 625,000 elders who were mainly from low-income groups14. Singapore, on the other hand, introduced a national long-term care insurance scheme, CareShield Life. This would help fund LTC provisions through premium payments that are deducted from a compulsory national medical savings scheme funded by member contributions15. Through the scheme, Singaporeans would receive lifetime coverage as well as monthly payouts if they met a minimum threshold of assisted living needs16, with lower income individuals receiving more support.

Strategies and Policies

In terms of blueprints, all three countries have taken steps to put in place national plans for LTC development in recent years. In 2023, the Ministry of Health in Singapore updated their 2015 Action Plan for Successful Ageing to account for post-pandemic changes17. Singapore also developed a USD 18 million Community Care Digital Transformation Plan in the same year to integrate assistive technology into their LTC provisions18.

Indonesia launched a National Strategy on Ageing in 2021 to implement a national funding strategy for LTC focused on four policy themes: social security, long-term education, empowerment programmes and integration. In 2024, Indonesia also announced the Road Map on the Care Economy, which has plans to direct funding to developing and expanding areas including LTC, care for persons with disabilities (PWD) and early childcare19.

Post-pandemic in 2021, in line with the government putting the elderly as a priority target group, Vietnam released a National Program of Action on Ageing to specify the responsibilities of relevant ministries from 2022 up to 203020. This national programme runs alongside their pre-existing Law on the Elderly that outlines that care should be primarily provided for by family members and that government aid should be provided when the elderly are without caregivers, disabled or poor.

Home- and Community-Based Care

All three countries have also been piloting different programs in home and community-based LTC. For example, there have been 100,470 healthcare posts by Indonesia Elderly Integrated Services serving 2.5 million elderly with health outreach, counselling and referrals21. However, a majority of these were disproportionately serving those in East Java compared to other provinces although expansion projects are still being undertaken22. As of 2021, there are no legislations providing allowances or working flexibility to accommodate workers caring for elderly relatives in Indonesia23.

For Singapore, a majority of seniors age in place at home (97%) due to preference, either in the care of family or alone. In order to ensure senior-friendly living conditions, the government provides subsidies for approximately 90% of costs to retrofit housing for the elderly24. For those who require supervision while caregivers are at work, centre-based day care services are provided, overseen by a national care integrator agency under the Ministry of Health25. These centres are located within the community, typically providing non-medical, personal care and social activities for healthy seniors or custodial care for those with dementia26. As at 2021, a small percentage of Singaporean elderly reside in nursing homes (2.5%), and the government has made efforts to integrate health and social care in underprivileged communities through pilot LTC programmes27.

Outside of family care, Vietnam offers various public and private LTC services for elderly. There are 3,442 Intergenerational Self-Help Clubs in 61 provinces, serving about 17,000 elders in home and community-based social care under the Viet Nam Association of the Elderly28. As of 2016, health counselling services are also offered in 270 communes in 32 provinces by 4,492 volunteers by the Ministry of Health and General Office for Population and Family Planning29. Although limited in reach, 134 residential centers run by the Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs serve 2,458 elderly with food and shelter30. Additionally, there are 36 provincial nursing and rehabilitation hospitals and 32 nursing homes as well as some privately run residential homes.

However, compared to public services these private nursing homes are often too costly for the elderly in Vietnam31. Projects to expand LTC reach have included the Korea-ASEAN funded collaboration to provide home-based LTC by volunteers and the Asian Development Bank approved project Strengthening Developing Member Countries’ Capacity in Elderly Care in 6 countries, including Vietnam32.

Looking Back at Malaysia

While Malaysia is faced with an increasingly ageing population, LTC facilities in the country are limited. Similar to the three aforementioned countries, publicly funded LTCs are only for the destitute in Malaysia. Government policy has been focused on establishing social support services within the community alongside a cultural preference to age in place. As a result, for others who need it, only a highly privatised care sector is available, which raises issues of affordability. This issue of cost is especially pertinent for those dependent on the “sandwich generation” of working adults, those who have to bear the burden of care for both young children and elderly parents.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Singapore appears to have made more substantial investments into their LTC ecosystem, in line with their significantly higher elderly dependency level. In comparison, Vietnam and Indonesia still face issues of availability and accessibility, perhaps also due to their lower income status and geographical spread of their population.

In establishing our own Care Framework, the Malaysian government must assess the needs of our own population and draw lessons from implementation in regional peers. This includes ensuring adequate care infrastructure, promoting the expansion of the care workforce and exploring ways in which care can be made affordable for the elderly33. Equally important is recognition of family-based caregiving and ensuring that sufficient support, both monetary and non-monetary, is provided. With ageing being a predictable life-course contingency, we should not wait until old-age dependency ratios are alarmingly high before acting.

.avif)

.png)

.png)