For policymakers in ASEAN, the immediate goal of attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to boost employment often obscures a longer-term structural danger: the middle-income technology trap. While attracting Tier 1 suppliers operating as Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) increases trade and employment in the short run, relying on this function as a permanent development strategy leads to a dead end.

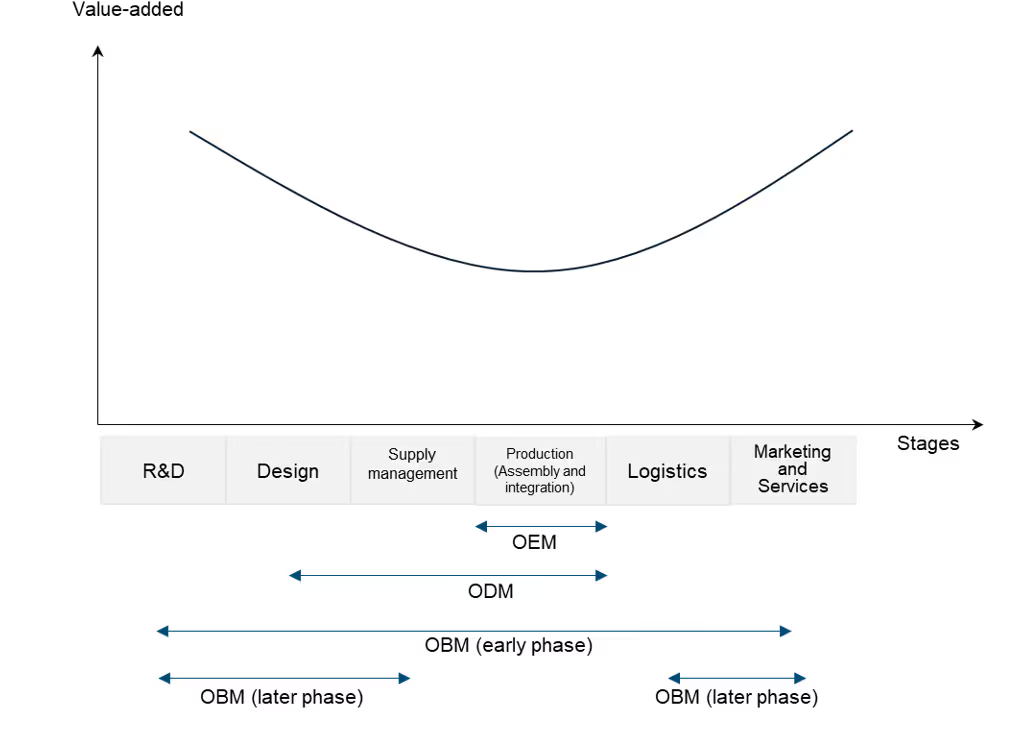

The activities that allow for high value extraction—and consequently high wages—are R&D, product design, and branding. Tier 1 suppliers, by contrast, face a low ceiling. They are contracted primarily for cost arbitrage. If a Malaysian or Thai OEM increases wages significantly, the lead firm will simply move the contract to a lower-cost jurisdiction like Vietnam or India. The threat of losing contracts imposes a structural wage ceiling, determined by the "next best" alternative location.

Even technological upgrading within this subordinate role has limits. As observed in China’s Pearl River Delta, firms that upgrade from OEM to Original Design Manufacturing (ODM) often still pay employees near minimum wage, relying on flexible labor regimes to maintain the razor-thin margins characteristic of the competitive supplier market, as documented by sociologists Boy Lüthje and Florian Butollo. Functional upgrading without brand ownership does not grant the market power necessary to significantly raise living standards.

Crucially, the nationality of the firm dictates the ceiling of this upgrade. Foreign-owned FDI subsidiaries have little incentive to evolve into global brands within the host country, as doing so would cannibalize their parent company's market. Their competitive advantage lies in mobility; if a host country becomes too expensive, they do not upgrade—they leave. In contrast, domestic firms are "sticky"; they cannot easily relocate their entire base. Faced with rising home costs, their only survival strategy is to move up the value chain. Thus, the transition to high-income status depends not only on the ambition of indigenous capital, but on the resources available to firms, their capacity to navigate structural challenges, and the availability of incentives to support this transformation.

However, the path for indigenous capital is obstructed by structural barriers often described as "production lock-in" and the "missing middle." From a learning perspective, when local firms commit their scarce resources to specific assets for unsophisticated activities—such as basic assembly—they often find themselves in a capability trap. These assets offer limited opportunities to learn the complex engineering or design skills required for upgrading. Consequently, firms remain stuck in low-value segments, lacking the intersectoral capabilities to pivot when cheaper competitors eventually emerge. This creates a structural polarisation: ASEAN economies are often split between large foreign MNCs and tiny, low-tech micro-enterprises. There is a critical lack of medium-sized domestic firms that possess the scale and skills to provide reliable intermediate products. Without these firms, the industrial system remains fragmented, and local enterprises lack the resources to invest in the technological upgrading required to break out of basic assembly.

To break this lock-in and bridge the capability gap, ASEAN countries must look to the "catch-up" strategies historically employed by South Korea and Taiwan. This typically involves moving through the three-stage framework described by innovation scholar Michael Hobday: from OEM (assembly), to ODM (design), and finally to OBM (Original Brand Manufacturing).

Yet, we must avoid a simplistic interpretation of this trajectory. As development economists warn, simply targeting the high-value ends of the "Smile Curve" (branding or R&D) is insufficient if a firm lacks the underlying production capabilities. True upgrading is multidimensional; it requires developing a complementary set of capabilities across the value chain. This is why upgrading into a specialised, monopolistic supplier—the "TSMC model"—is an equally viable path to high income. In this model, the firm does not seek to create a consumer brand but instead dominates a critical, high-barrier node in the global value chain through deep process innovation. Whether the goal is to become a Samsung (OBM) or a TSMC (dominant supplier), the requirement remains the same: the development of proprietary, non-substitutable technology.

For those attempting the OBM route, this transition is not a peaceful evolution; it is a fight for independence. As noted by Keun Lee and colleagues, when a supplier attempts to launch its own brand (OBM), incumbent lead firms often retaliate. They may cut orders to destroy the cash flow of the emerging competitor, file IP lawsuits, or engage in predatory pricing. This conflict contradicts the optimistic "win-win" view often found in GVC literature. Upgrading requires a struggle against the very lead firms that facilitated the initial industrialisation.

Crucially, this upgrading process follows an "In-Out-In" pattern theorised by Lee and colleagues, which has profound implications for intra-ASEAN trade.

1. In (OEM phase): Firms link to GVCs to acquire process technology and operational skills. At this stage, Foreign Value Added (FVA) is naturally high, as the firm relies heavily on imported components and designs from the lead firm to execute assembly.

2. Out (Early OBM phase): To become OBMs, firms must "delink" from the lead firm to build domestic capabilities in design, R&D, and branding. This phase is defined by a structural shift in value creation: firms actively reduce their Foreign Value Added (FVA)—the reliance on imported inputs—in favour of Domestic Value Added (DVA). While this substitution may temporarily dampen trade volumes as firms detach from established global supply chains, it is a necessary contraction to build the indigenous capabilities required for high-income status.

3. In (Late OBM phase): Once the OBM succeeds and creates its own market power, rising domestic production costs drive it to internationalise its supply chain again. Unlike the first phase, where market access was passive and dependent on a foreign lead firm, the firm now re-enters the global market as a lead firm itself, actively controlling global distribution channels and sourcing networks to maximise efficiency.

It must be acknowledged that the "Out" phase is exponentially more difficult today than it was in the late 20th century. The consolidation of global intellectual property and the sheer complexity of modern technologies—such as advanced semiconductors or AI—make total "delinking" nearly impossible. ASEAN firms cannot simply copy-and-paste the Samsung model of the 1980s. Instead, they must find specific niches or "short-cycle" technologies where the barrier to entry is manageable, accepting that partial dependence on global tech stacks will persist. To overcome these formidable barriers, state support becomes indispensable. Governments must actively nurture local firms—whether through government-linked companies (GLCs) or supported private conglomerates—to achieve the minimum efficient scale required to compete with global incumbents. Small enterprises simply lack the R&D budgets and litigation war chests to survive the 'Out' phase. It is not necessary for every domestic firm to make the leap into OBM; historically, the emergence of a handful of 'National Champions'—like Samsung in Korea or Toyota in Japan—is sufficient to fundamentally alter a nation’s economic trajectory.

Despite the difficulty of this upgrading process, large ASEAN nations cannot simply rely on the easier path of hosting foreign MNCs, as exemplified by Singapore. Critics might point to Singapore as proof that a nation can achieve high-income status primarily by hosting foreign MNCs rather than creating indigenous global brands. However, this model relies on the specific fiscal arithmetic of a city-state. Singapore’s small size and population allow it to sustain development through a low-tax, high-FDI model that functions as a regional service hub. For populous, geographically vast nations like Indonesia, Vietnam, or Thailand, this 'offshore hub' model is structurally unviable to replicate. They cannot generate sufficient fiscal revenue from such low taxes or create high-value employment for millions of people across large territories. For these larger nations, the wealth required for mass development must come from the deep value capture of broad-based industrialisation—which requires owning the production, the technology, and the brand.

The Endgame: A New Pattern of Trade

If successful, this transition will fundamentally reshape regional trade patterns. As ASEAN firms effectively upgrade to OBMs and gain significant stakes in international markets, trade between them and their neighbours is likely to increase, driven by two key factors.

First, as production costs in the home country of the successful OBM rise, these firms will naturally seek lower-cost sites for assembly and component manufacturing. An Indonesian OBM, for instance, might retain high-value design in Java but outsource assembly to Myanmar or Laos, creating a sustainable, regionally integrated supply chain.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the success of OBMs creates wealth. As these firms become engines of their national economies, they foster a large, affluent middle class. This middle class will demand diverse final products—not just from the West or East Asia, but from neighbouring ASEAN countries that have also successfully created international brands. Intra-ASEAN trade thus shifts from the mere movement of intermediate parts to the exchange of high-value final goods.

In the long run, as the entire region develops, the sourcing of the lowest-value intermediate inputs may even shift to other regions, such as Africa, if it becomes more economical to produce them there. This would leave intra-ASEAN trade focused on high-value exchange and consumption, marking the region's graduation from a global factory to a global market.

Thus, sustainable intra-ASEAN trade will only be driven by ASEAN-owned OBMs that are politically and technologically savvy enough to navigate these new hurdles. Trade liberalisation alone cannot achieve this. It requires an industrial policy that supports local firms in navigating the perilous "Out" phase—providing the R&D grants, patient capital, and protection needed to survive the counterattacks of global incumbents.

Finally, the success of this strategy hinges on the underlying political settlement. As Mushtaq Khan argues, effective industrial policy is not merely a technocratic exercise but a political one. It requires a distribution of power where the ruling coalition can enforce performance standards on the recipients of state support. Rather than simply decrying clientelism, ASEAN nations must forge a "growth coalition" where powerful social groups—business elites, political leaders, and labour—reach a consensus to direct rents towards productive accumulation and learning rather than short-term consumption. Without this alignment of interests to discipline underperforming firms, industrial policy becomes a mechanism for waste. Thus, ASEAN’s economic goal must shift from simply being a site of production for others to developing the political and industrial capacity to control the production itself. Only then will trade be a driver of wealth, rather than just a metric of activity.

.avif)

.avif)