Introduction

The findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2024 reveal that a staggering one in three adolescents, or more than 30% of children between the ages of 5 and 17 years in Malaysia was classified as overweight or obese in 20221. In this context, children are classified as individuals younger than 18 years, whereas adolescents denote those in the 13 to 17 age group.

In today’s fast-paced digital landscape, children’s dietary habits have undergone a dramatic shift. The pervasive influence of social media, combined with the convenience of various food delivery services, has transformed not only how Malaysians discover food but also how children form their dietary preferences2.

The digital environment is saturated with advertisements, influencers, and online promotions3, and how all these play a significant role in shaping health behaviours among young Malaysians has become increasingly concerning.

In July 2025, the Ministry of Communications stated that it is considering prohibiting social media accounts for children under the age of 13 due to harmful content involving children4. Three months later, in October 2025, the Communications Minister announced that the cabinet is weighing the proposal to raise the minimum age of social media use from 13 to 165. While the main objective of the social media ban is to protect children from harmful content, such as “brain rot”6, paedophilia, cyberbullying, and scams, there may be additional impacts on children’s dietary habits, considering the growing influence of digital exposure on dietary knowledge and behaviour. Hence, this article aims to explore the potential social media ban from another angle, and to open up another policy question: Could the solution to childhood obesity lie in curbing access to these digital platforms?

Negative Influences of Digital Food Environment on Children’s Diets

Children’s food choices are typically influenced by a combination of several factors – biological factors, family systems and influences, environmental factors, and media exposure7. In the digital era that we are living in today, these influences are increasingly mediated through digital food environments—online spaces where information and services related to food are delivered, and these environments play a significant role in shaping individuals’ dietary choices and eating behaviours8. The key components of the digital food environments include social media platforms, online health promotion initiatives, digital food marketing, and online food retail or delivery services.

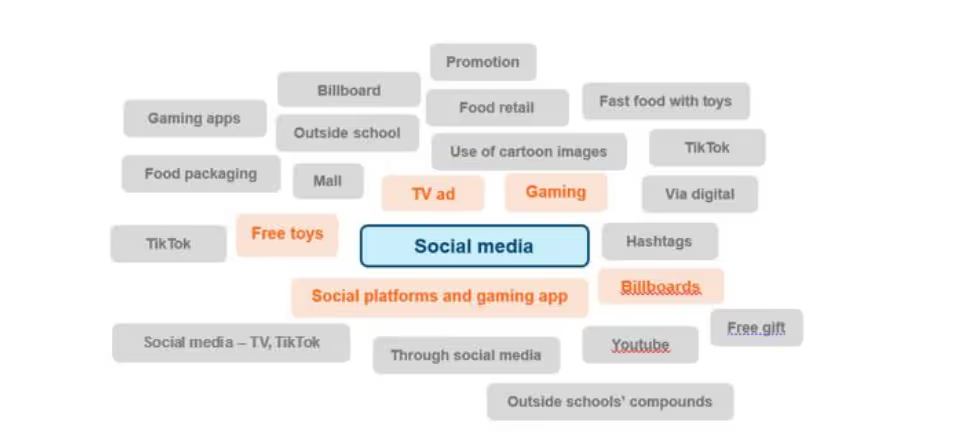

Extensive food marketing on social media platforms has become a significant determinant influencing dietary behaviours in children9. Findings from previous research revealed that social media is the most frequently utilised approach for promoting unhealthy foods and beverages to children in Malaysia, as shown in Figure 110. This is exacerbated by the fact that digital marketing is largely supported by complex technology platforms and algorithms that automate the buying and selling of targeted advertising impressions. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult to identify the intended audience of these advertisements. Children, who are still developing the cognitive skills to distinguish advertising from entertainment, are especially vulnerable to persuasive and often unhealthy food promotions.

Figure 1: Frequently utilised approach for promoting unhealthy foods and beverages to children in Malaysia

According to UNICEF’s Report on Use of Social Media by Children and Adolescents in East Asia (2020), 90% of children in Malaysia aged between 5 and 17 are internet users, while 92% of students aged 13 to 17 have social media accounts11. Social media refers to online applications and websites that allow users to create and share content, participate in online communities, and interact with others through the internet. Among the popular social media platforms used in Malaysia are TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, where children spend a considerable amount of time on these platforms. A 2024 study shows that 65% of Gen Alpha children between the ages of 8 and 10 spend up to 4 hours a day on social media alone12.

While much of the attention on social media’s harmful impact on children centres around unhealthy food marketing, other concerns are equally significant. These include the spread of misinformation, targeted advertisements for unhealthy foods and beverages that not only promote poor dietary habits but also contribute to body image issues. Additionally, the use of personalised ads and algorithm-driven content makes digital marketing more pervasive and convincing than ever before. As food marketing has evolved into entertainment, social media marketers seize this opportunity to promote unhealthy foods and beverages to children on social media with several tactics. For example, engagement with famous influencers to create engaging videos featuring fast foods, instant noodles, and sugary snacks.

Social media forms or content, such as Instagram reels and TikTok “mukbang”13 videos frequently feature visually appealing food presentations and promotional offers to entice their viewers. Another popular marketing tactic that is widely used is the Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR), in which marketers or influencers create videos with sounds, such as the crunching of chips or the sizzling of fried chicken, to evoke a sensory response in viewers, making them hungrier and more tempted to try the food being displayed. Furthermore, marketers also utilise attractive advertising tactics, including stickers, geotags, hashtags, and brand recognition, to promote unhealthy foods and beverages to children on social media. Exposure to digital food marketing is consistently associated with food intake or preferences. Previous research indicates that greater exposure to unhealthy food marketing on social media platforms is associated with increased preference for and consumption of those products14.

Due to their developing cognitive abilities, children are particularly vulnerable to social media influences. They may struggle to make a difference between advertisements and organic content, making it difficult for them to recognise the commercial intent behind advertisements and to resist impulses or behaviours that may lead to temporary pleasure but long-term health consequences15. This vulnerability is exacerbated by children’s tendency to be influenced by their peers and online personalities than by traditional authority figures.

Would a Social Media Ban Improve Children’s Diet?

The proposed social media ban for children under 16 aims to protect minors from exposure to harm caused by online sexual exploitation or abuse and cyberbullying. It is hoped that by the age of 16, most teenagers would have developed a better sense of judgement, clearer social boundaries, and stronger emotional regulation that can protect them as they navigate the unfiltered nature of social platforms16. From a health perspective, the ban on social media carries both potential benefits and limitations in addressing childhood obesity in Malaysia. On one hand, the ban could reduce children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing, advertisement and misinformation on social media platforms, potentially mitigating the influence of these harmful marketing messages on their dietary choices. Children may be less likely to encounter unhealthy food advertisements for sugar-sweetened beverages, processed and fast foods, through limited access to social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram. On the other hand, imposing a complete social media ban may be disproportionate. A more balanced and effective approach would be to strengthen regulations governing digital marketing, a policy area that currently lacks sufficient oversight and enforcement.

The measure to ban social media may fall short in several aspects:

First, if children under 16 were barred from using these platforms, would they truly be shielded from persuasive marketing, or would these messages simply shift to other forms of media, such as television, gaming platforms, or outdoor marketing? Despite the ban, children may still be exposed to unhealthy food marketing through alternative channels, potentially undermining the ban’s intended effectiveness.

Secondly, implementing and enforcing a social media ban can be challenging, as many children under 16 have already bypassed social media registration restrictions through parental or shared accounts, or by falsifying their birth year.

Third, a full social media ban for children could also bring some negative consequences that should be taken into consideration. Without social media, children can feel isolated and disconnected from the world around them, which could lead to other unwanted problems, such as mental health issues. Social media platforms are so much more than merely entertainment. These platforms are also the spaces where children pick up new knowledge, share ideas, and stay in touch with family and friends. Studies have shown that platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, when used for educational purposes, may contribute to language development and memory enhancement17. Therefore, the abrupt ban of social media could affect their social development and impede their growth and learning.

Childhood Obesity in Malaysia Explained

Obesity can be described as a medical condition where there is an abnormal and excessive accumulation of body fat, often determined using the Body Mass Index (BMI). If a child’s BMI falls between the 85th and <95th percentile in the WHO growth chart, the child is categorised as overweight. A BMI at or above the 95th percentile indicates obesity in the child (WHO 2007).

Childhood obesity is a multifaceted condition, often resulting from the interplay between genetic predisposition and lifestyle factors. Research examining risk factors across six critical life stages—pre-conception, prenatal, infancy, preschool, school age, and adolescence—suggests the key contributors to childhood obesity include genetic factors, maternal health and behaviours, dietary habits, level of physical activity, sleep patterns, socioeconomic conditions, and environmental influences18.

The National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (NPANM) III data reveal a troubling trajectory. Within 4 years from 2011 to 2015, childhood obesity nearly doubled, from 6.1% to 11.9% (Figure 2). The latest data in 2019 showed that 15% and 14.8% of children aged 5 to 17 were overweight and obese, respectively19. If the rising trend of childhood overweight and obesity is not reversed, the World Obesity Atlas 2024 report forecasts that by 2035, 65% or 5 million children in Malaysia will be overweight or obese20, highlighting the need for immediate intervention. Children who are obese or overweight tend to face an elevated risk of remaining overweight in adulthood compared to their peers with a healthy weight21.

Figure 2: Prevalence of obesity (BMI for age > 2SD) by age groups in Malaysia

Malaysia is known for being a food haven, with a wide range of cuisines that are too hard to resist and to choose from; however, unhealthy food intake, alongside inadequate sleep and a lack of physical activity, contribute to Malaysia’s rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in general23. The average Malaysian dietary intake is characterised by elevated levels of sugar, salt, and oil, with low daily intake of fruits and vegetables24. For example, the all-time favourite Malaysian breakfast, Nasi Lemak paired with Teh Tarik is highly affordable, but also often packed with calories, sugar and fat. Consuming them excessively in the long run can contribute to an expanded waistline and other concerning health problems.

According to the Health Technology Review by MOH in 2017, there was a fair to good level of retrievable evidence to suggest that unhealthy foods and beverages marketing increased energy intake and children's preference towards advertised food25. While reducing children’s exposure to unhealthy marketing through a social media ban might seem like a straightforward solution, it is important to recognise that obesity in Malaysia is not driven by digital influence alone. A ban on social media might alleviate one pressure point, but without tackling these broader factors, its effectiveness would likely be limited. This highlights the importance of implementing proactive measures to promote healthy dietary and lifestyle choices early in life, ensuring a healthier future for all children.

Global Lessons on Regulating Food Marketing

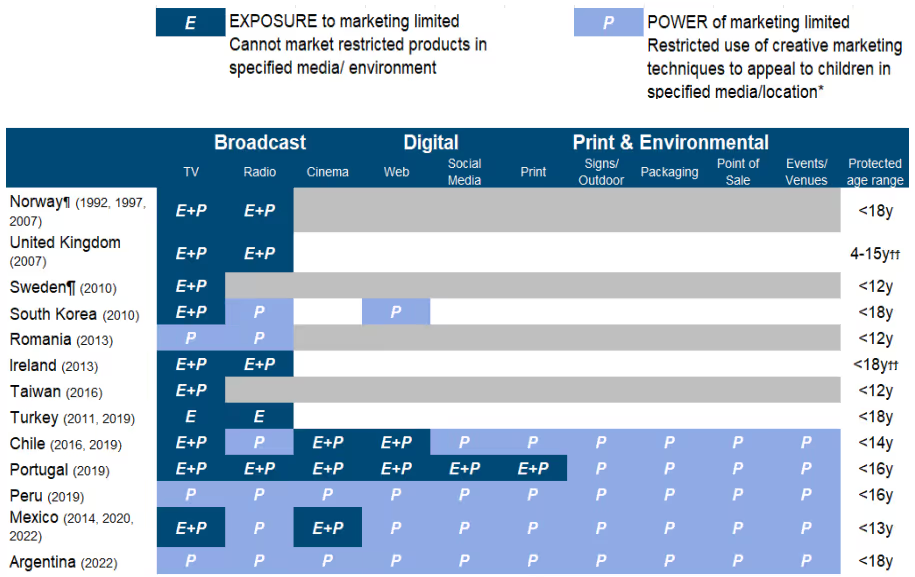

According to a review by the Global Food Research Program in 2024, thirteen countries have introduced various policies regulating food marketing to children26. Though these policies vary in scope and stringency, they aim to protect children from unhealthy foods or beverages marketing. Unhealthy food and beverages are commonly determined using a nutrient-profiling system that classifies foods according to their nutritional composition—by identifying foods high in fat, sugar, salt (HFSS), and calories, and evaluating the content of beneficial components, such as dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

Out of the 13 countries, only five countries have implemented comprehensive policies that restrict food marketing to children across different media—broadcast, digital, print and environmental media27, as summarised further below. An overview of the restrictions of the food marketing restrictions implemented in the five countries is shown in Figure 3.

• Chile (Introduced in 2016 & updated in 2019)

Chile’s Food Labelling and Advertising Law (Law 20.606), which was passed in 201628, is one of the world’s most comprehensive and has become a model for other nations. In 2016, almost half of the child population in Chile was overweight or obese29. The Law prohibits the exposure of restricted food products on broadcast media, such as television and cinema, as well as digital platforms, including websites and social media, that attract a high number of child users. Additionally, it limits the use of creative marketing techniques that appeal to children below 14 years of age across all media, including print and environmental advertising. A 73% drop in children’s exposure to TV ads for regulated foods and beverages was observed after the implementation of the law in 201630. The 2019 amendment to the law introduced restrictions on the broadcasting hours of “high-in”31 advertisements, banning them from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily, which subsequently led to a 67% reduction in children’s exposure to food and beverage marketing compared to the period before the regulation was implemented32.

• Portugal (2019)

Law No. 30/2019 was enacted in 2019 in line with the World Health Organization’s recommendation to promote healthy eating and to prevent and control obesity. The Law restricts the marketing of foods and beverages with high energy content and salt, sugar, saturated fatty acids, and trans fatty acids to children under 16 years old. The policy restricts the exposure of marketing across schools, public playgrounds, television, radio, cinema, digital media—including websites and social media—and print and environmental media33. The latest data in a 2022 survey indicated an improvement in children’s eating habits after the implementation of the regulation, with over 80% of children reporting that they consumed fresh fruit and vegetables at least 4 times a week34.

• Peru (2019)

Law No. 30021 on the Promotion of Healthy Eating for Children and Adolescents, which was passed in 2013 and implemented in 2019, is among the few policies in Peru designed to address childhood overweight and obesity. According to a UNICEF (2023) report, these issues have become major public health concerns, with 8.6% of children under five classified as overweight or obese, and prevalence rates reaching 38.4% among children aged between 6 to 13 and 24.8% among adolescents35. The law requires that all advertisements for processed foods that are high in sodium sugar, saturated fats, and trans-fat content, to clearly display warning labels on screen. It also restricts the use of persuasive marketing techniques aimed at children under 16 years old across print media, radio, and audiovisual media, including video and television36.

• Mexico (Introduced in 2014, updated in 2020 and 2022)

Mexico has adopted a series of progressive regulations limiting the creative techniques of unhealthy food marketing to children under 13 years of age across all media, and limits exposure to restricted products on television and cinema. In 2014, Mexico’s Ministry of Health amended the General Health Law on Advertising to regulate food and beverage marketing to children, prohibiting advertisements of unhealthy foods between 2.30 p.m. and 7.30 p.m. on weekdays and between 7 a.m. and 7.30 a.m. on weekends, based on the statistics that at least 35% of the audience is under 13 years old37. This amendment complements the 2020 revision of the Mexican Official Standard NOM-051 (Front of Pack Labelling) regulation, which mandates marketers to display warning labels indicating excessive levels of sugar, salt, fat, or calories in prepackaged food and non-alcoholic beverages. Additionally, advertisements shall not use any characters such as cartoons, animations, or interactive elements that are appealing to children38. A 2022 update further strengthened the enforcement by requiring marketers to obtain prior authorisation from the relevant Mexican authorities before placing an advertisement39.

• Argentina (2022)

Argentina is the most recent country to restrict the use of creative marketing power of unhealthy foods that use certain techniques, such as cartoons, animation techniques, and celebrities, to children across all media platforms. It is also the only country with the highest restriction age limit of 18 years old40. In 2021, Argentina enacted Law No. 27.642 on the Promotion of Healthy Eating (Front-of-Package Labelling Law), followed by its implementing regulation Decree No. 151/2022 in 2022. The regulation mandates the use of black octagonal warning labels on packaged food and beverages that are excessive in sugar, sodium, saturated fat, and total fat, to help consumers identify products that are nutritionally unbalanced41.

Figure 3: Media channels and environments covered by policies

Note: *”Power” restrictions differ across policies but generally prohibit the use of persuasive marketing techniques such as offering gifts, toys, or prizes, or using cartoons, characters, or celebrities to attract children (with age limits defined by each policy)ϯFor clarity, digital marketing categories are simplified here. Digital marketing can appear across various formats including company-owned websites, paid advertisements on third-party platforms, mobile apps beyond social media, and video or online games. ϯϯSome countries apply different age ranges are used for restrictions on creative marketing techniques. For example, Ireland limits the use of licensed characters, celebrities, or athletes, and promotional offers for children under 13 years; while in the UK, restrictions apply to children under 12 years for the use of licensed characters, celebrities popular with children, or promotional offers.¶Restrictions extend to all commercial products, and not only foods and beverages

Existing National Policy Frameworks

The statistics shown above call for more serious intervention and actions by the Government. However, calls for action are not something new, and guidelines that have been in place for over a decade, yet the problem persists. To improve the health of children and adolescents, the Ministry of Health Malaysia introduced two key frameworks—the Malaysian Dietary Guidelines for Children and Adolescents (MDGCA) and the National Strategic Plan to Combat the Double Burden of Malnutrition Among Children in Malaysia 2023 – 2030.

Together, these policies aim to foster an enabling environment for healthier growth and development in Malaysian children. However, ensuring consistent implementation of existing guidelines and policies across settings and communities remains a significant challenge. For these frameworks to achieve their intended impact, the recommendations must be reinforced through sustained advocacy and practical integration into daily practices. Although the policies provide clear guidance on promoting healthy and nutritious eating among children, their effectiveness is limited by a lack of sustained efforts, mandatory implementation, and enforcement42. This challenge is further compounded by the pervasive influence of unhealthy food marketing, particularly through social media platforms, which often contradict and undermine the core messages of national dietary guidelines. In this context, the proposed social media ban for children under 16 could be seen as one potential mechanism to reduce such exposure. However, without complementary efforts to strengthen public engagement, advocacy, and digital marketing regulation, the ban alone is unlikely to address the deeper structural barriers to healthier dietary behaviours among Malaysian children.

A few years back, Malaysia began laying the regulatory groundwork to address unhealthy food marketing; however, these measures are lacking in digital food marketing. Existing measures focus mainly on nutritional labelling, public education, and voluntary commitments from the industry, rather than mandatory restrictions. The Ministry of Health’s Guidelines on Labelling and Advertisement for Fast Food, introduced in 2008, require fast-food operators, advertising agencies, and broadcasting organisations to display mandatory nutrition information on food products, including energy, fat, carbohydrates, total sugar, and sodium content on food products. To safeguard children from exposure to unhealthy food marketing, the Guidelines prohibit the marketing of fast food on television during children’s television programming and restrict fast-food companies from sponsoring any children’s television shows43.

Additionally, the “Responsible Advertising to Children” (Malaysian Pledge) initiative was launched in 2013 by the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers Malaysian Food Manufacturing Group (FMM). Twelve Malaysian food and beverage industry players signed the pledge to demonstrate their voluntary self-regulated commitment to adopting responsible marketing practices directed at children below 12 years old44. However, the pledge is not mandated by law; therefore, the official monitoring of compliance is limited and depends entirely on the companies’ commitment to comply.

Subsequently, in 2024, MOH introduced the MyIklan Logo initiatives and is currently developing accompanying guidelines, which will be implemented on a voluntary basis in collaboration with the food and beverage industry, advertising companies, and broadcasters. This initiative is intended to improve public awareness of the risks associated with the consumption of foods and beverages that contain high levels of fat, salt, and sugar. The long-term goal is to transition from voluntary participation to a mandatory requirement, ensuring that all unhealthy food products are clearly labelled with the logo to improve consumer awareness and support healthier dietary choices45.

The initiatives mentioned above still lack focus on digital food marketing, which still remains a concern if children continue to be exposed to unhealthy food advertisements on the internet. Findings from previous research indicate that self-regulation and voluntary regulations are insufficient in reducing children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing46, particularly in fast-evolving digital environments. Therefore, strengthening Malaysia’s regulatory ecosystem to become mandatory and to include digital platforms would align national efforts with the more comprehensive regulatory models adopted in countries such as Chile, Portugal, and Peru. The integration of digital and traditional regulations would ensure that children are protected from unhealthy products in physical stores as well as from the pervasive digital marketing that shapes their choices of food.

However, a reformation of regulations is not without challenges. Government efforts are often met with strong resistance from industry stakeholders; whereby stricter marketing regulations could affect commercial interests. It can also be difficult to distinguish between paid marketing and user-generated content, influencer promotions, and algorithm-amplified posts. The blurred boundaries between the different marketing strategies can further complicate regulations and make it more challenging to be implemented and enforced.

Conclusion: Beyond the Ban

Unregulated and pervasive food marketing on social media can be a contributing factor to the rising rates of childhood obesity in Malaysia, but the root causes may be more deeply embedded—Malaysia’s cultural eating habits, urban lifestyles, and the affordability and accessibility of unhealthy foods. Therefore, addressing childhood obesity in Malaysia requires actions beyond isolated interventions, and more than banning social media for children under 16 of age. We need to call for a recognition of the complex interplay between modern digital influences and enduring cultural traditions that define Malaysia’s food environment.

Moving forward, Malaysia should look beyond limiting access to digital spaces and focus on reshaping the digital food environment that influences our diets. Extending existing labelling and marketing standards to digital platforms, curbing persuasive online advertising, and enhancing media and nutrition literacy among children and parents can collectively create a healthier and more informed digital ecosystem, which can help children recognise persuasive food marketing and make healthier food choices.

Ultimately, managing children’s obesity in Malaysia requires a double-pronged approach, by regulating digital food marketing while simultaneously instilling healthier eating habits. That said, the ban of social media for children under 16 will not fix the malnutrition problem; what needs to be done is to protect children from unhealthy food marketing through a unified and mandatory framework, and to create a food environment that supports healthier choices that align with the country’s broader vision of a healthier and digitally empowered society.