Introduction

Women’s participation in the workforce is not linear but interwoven with multiple intersecting factors. The paradox of women entering, exiting, re-entering, or never entering the workforce becomes particularly significant when policies aimed at increasing women’s labour force participation in Malaysia are being pursued more actively each year. In recent years, there has been a growing demand for greater women’s participation in the economy, as their inclusion is closely linked to global economic growth, poverty reduction, and improved access to high-productivity sectors1.

This conversation often leads to the question of where our educated women are, especially when women’s educational attainment in Malaysia has already surpassed that of men. However, instead of asking where these women are, the more important question is why many of them are unable to enter or remain in the labour force. A major factor to explain this is the expectation that women simultaneously fulfil family and work responsibilities. While policies call for higher women’s participation in the workforce, women are still predominantly positioned as default caregivers responsible for domestic and household duties. This expectation often forces women to navigate between traditional roles and formal employment, affecting how their contributions are recognised and valued in both spheres.

This article seeks to explore factors that led highly educated married women exit or do not enter the labour force despite having equal or higher educational attainment than their husbands. According to the latest survey from KRI in collaboration with Persatuan Suri Rumah Rahmah Malaysia (SRR), there are rising number of educated married women, however these highly educated wives still leave the workforce. The discussion does not intend to undermine the value of women who choose to be housewives; rather, domestic and caregiving responsibilities should be recognised as legitimate and meaningful forms of labour as advocated in the latest paper of KRI titled Interwoven Pathways: The Care and Career Conundrum in Women’s Empowerment2. However, understanding the motivations behind these choices can provide deeper insight into the factors that shape women’s participation in the labour force and challenge the stereotype of them as not participating contributing to the economy and nation.

Education as an Equalizer or Illusion of Equality?

There is strikingly high level of educational attainment in KRI-SRR survey, with 85.5% holding tertiary qualifications and only 13.5% possessing secondary education. Yet, despite this strong educational profile, these women remain outside the formal labour force. The finding that many tertiary-educated women are not in the labour force often provokes a seemingly straightforward question—why would someone invest in education but not use it in the labour market? This assumption rests on a one-way view of empowerment, where higher education is expected to translate automatically into greater economic participation. The overrepresentation of tertiary- educated housewives in our survey suggests that women’s withdrawal from paid employment is not primarily due to inadequate qualifications but reflected due to deeper structural and social disjuncture between women’s educational advancement, social norms and the realities of labour market and household economy.

In many middle-income contexts, women’s labour force participation does not rise smoothly with education—it often bends into a U- or J-shaped pattern. The patterns illustrates that women’s participation tends to be high at lower education levels due to economic necessity, declines as education level and household income rise, and increases again among highly educated women who gain access to better employment opportunities3. The “J-shape” captures this stronger recovery at higher education levels, showing that education helps only when paired with supportive workplaces, affordable care options, and cultural acceptance of women’s paid work4.

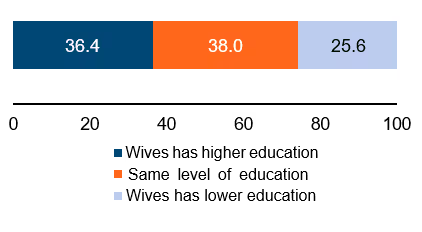

In looking into the gender gap between men and women in the labour force, we dive into looking at the participation between wives and their husbands based on our findings in the survey. Figure 1 shows the level of education between wives and husbands; 38% has the same level of education, followed by 36.4% more educated than their husbands, and 25.6% of those has lower education than their husbands. Notably, a majority (72.7%) of these women possess equal or higher education than their spouses.

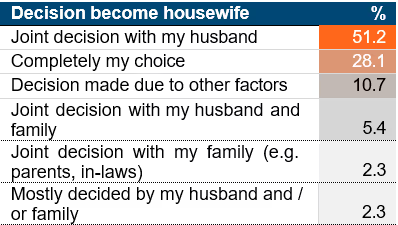

While this does not allow us to conclude why these women are currently housewives, the pattern is noteworthy as one might typically expect higher education to be associated with labour force participation. Figure 2 sheds further light on the decision-making process behind becoming a housewife. Among tertiary-educated respondents, slightly more than half (51.2%) reported that the decision to stop working was made jointly with their husbands, while 28.1% stated it was entirely their own choice. A smaller proportion attributed the decision to other external factors (10.7%), while about 10% reported decisions made jointly with or influenced by family members (e.g., husband, family, in-laws, parents, etc.)

Figure 1: Education level between wives and husbands

Figure 2: Respondents' decision to become housewife

These responses suggest that, for most tertiary-educated women, the transition into a housewife role is not solely imposed but negotiated within household relationships, with varying degrees of individual agency. When compared to non-tertiary educated women, the overall trend remains similar—joint decision-making with the husband is the most common response across both groups. While non-tertiary educated women show slightly higher shares reporting individual choice (34.2%) and decisions influenced by other factors (12.5%), these variations should be interpreted with caution given the smaller sample size for this group5. Nonetheless, the pattern suggests that across education levels, most women describe the shift into a housewife role as a shared or self-initiated decision, rather than one predominantly imposed by others.

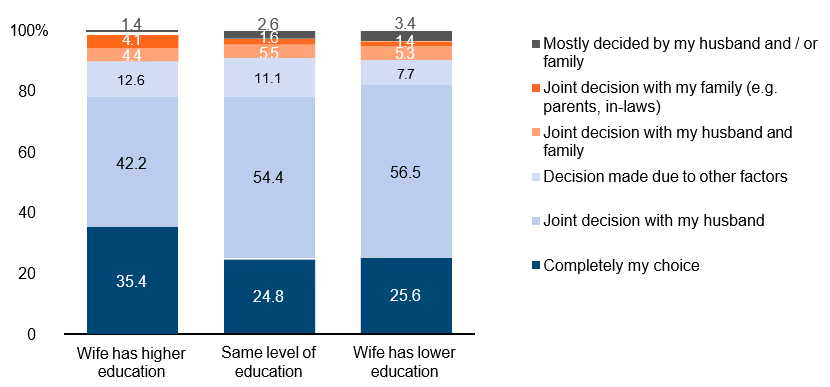

When examining this decision-making pattern by women’s education relative to their husbands, notable nuances emerge in Figure 3. Women who possessed higher educational attainment than their husbands showed a slightly greater sense of personal agency, with 35.4% reporting that the decision to become housewife was entirely their choice, though the largest share (42.2%) still described it as a joint decision with their spouse. In contrast, women with lower educational attainment than their husbands reported the highest share of joint decision-making with husband (56.5%), suggesting that the decision was more often framed as a shared household choice in these situations.

These findings show that even highly educated women, despite strong credentials, the decisions about work remain relational and negotiated within families, and social expectations shape their engagement in paid work. It highlights how gendered expectations influence women’s time, choices, and labour force participation. This dynamic can showcase push factors in labour force and becomes more apparent when examining the distribution of care responsibilities within households, which will be further illustrates.

Figure 3: Decision to become housewives based on level of education with their husbands

Push factor: Juggling paid work and care responsibilities

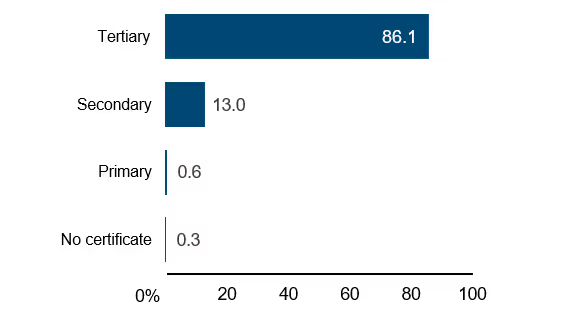

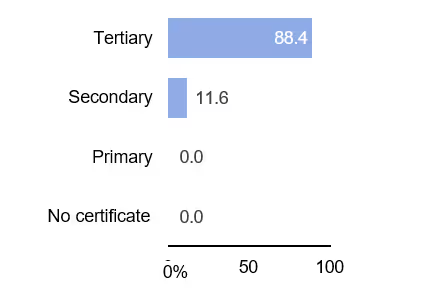

Although many women work to support their families and make use of their education, they continue to take on most of the responsibilities at home. Among respondents who had previously been in the labour force but have since stopped working, disaggregation by their education level shows that most are tertiary educated (86.1%), followed by those with secondary education (Figure 4). This pattern may partly reflect our survey sample composition, as the largest shares surveyed women hold tertiary qualifications. However, when comparing across education groups, the non-tertiary educated respondents are more likely to have never worked at all. This suggests that while higher education facilitates entry into paid work, it does not shield women from the structural and familial responsibilities that contribute to their eventual exit.

Despite being qualified and previously in full-time employment, many women continue to withdraw from the labour market as it coincides with the enduring structural and cultural constraints. These include the incompatibility of full-time work with caregiving and domestic responsibilities, systemic barriers in the labour market, and the unmet wage returns for their human capital investment.

Figure 4: Respondents who has worked before but has since stopped by educational attainment

In recent discussions, the social dimension of care has been increasingly emphasised. For instance, maintaining the dignity and quality of life of care recipients particularly elderly are believed to be enhanced when they can remain in familiar environments and be cared for by family members6. However, such perspectives often overlook the opportunity costs borne by caregivers predominantly women if it does not come with viable support. Beyond the psychological, physical, and social tolls, caregivers also face forgone earnings, reduced productivity, and workplace absenteeism, all of which have long-term implications for their economic security and wellbeing7.

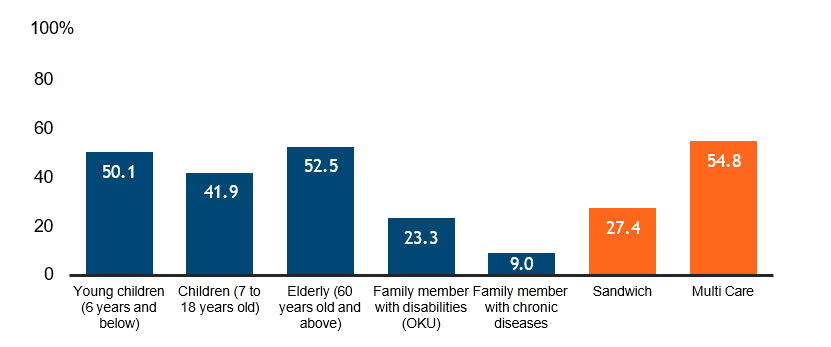

Figure 5 illustrates the breakdown of care recipients of tertiary-educated respondents, shedding light to the reasons they remain outside the labour force or are unable to participate fully due to caregiving responsibilities. The data show that care for elderly family members (52.4%), young children aged 6 and below (50.1%) and children aged 7 to 18 (41.9%) are among the most common caregiving responsibilities. Caring for both children and the elderly (i.e. the “sandwiched” generation is also common (27.4%).

Some respondents also care for family members with more complex or specialised needs. About 23.3% reported caring for a person with a disability, while 9.0% cared for someone with a chronic illness. Such responsibilities demand substantial time, emotional energy, and physical effort, and often require specialised knowledge. Consequently, these duties place a heavier burden on primary carers, most of whom are women. Overall, 54.8% of housewives reported having a multi care where there is more than one type of dependent, underscoring the intensity of caregiving demands within these households.

Figure 5: Breakdown of the type of care recipients

2. Sandwich generation = Respondents who care for both children (below 18 years old) and elderly individuals (60 years or above). Multiple care recipients = Respondents who have two or more types of care recipients.

3. The classification under type of care recipient reflects the different categories of individuals for whom care is provided. Some household members may fall into multiple categories. For example, a disabled child may be counted under both the child and disabled categories, while an elderly person with chronic illness may be considered both an older adult and someone with a chronic health condition.

Push factor: Trade-Offs Between Career, Pay, and Family Life

Previous studies, particularly cross-country analyses in regions such as East and South Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, have found that higher household income and male educational attainment are often linked to lower female labour force participation. This pattern, sometimes referred to as the “household-status effect,”8 suggests that in some cultural and socio-economic contexts, a woman’s withdrawal from paid work is viewed as a marker of household stability and respectability9.

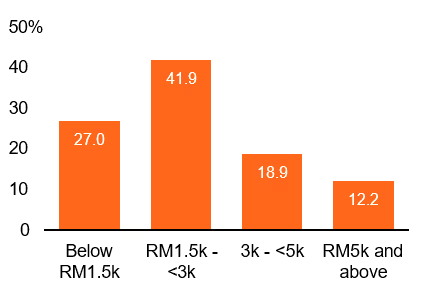

However, this effect cannot be generalized, as it risks overlooking the burden of unpaid care and domestic work carried by women. The notion that a family can “afford” a non-working wife is further challenged by our findings: among tertiary-educated women who have left their jobs to become housewives, 47.8% belong to B40 households, 39.9% to M40, and only 12.4% to T2010. For many women, leaving the workforce is not a choice of privilege but a necessity driven by caregiving demands and limited support. Balancing unpaid care with insufficient household income places them at heightened social and economic risk, especially when they care for multiple dependents with diverse needs.

Building on the earlier analysis of respondents who had worked before but have since stopped (Figure 4), we now turn to those who have worked previously but are currently engaged in part- time work. Among this group, a large share, 88.4%, are also tertiary educated (Figure 6)11. Within this context, tertiary-educated women show a higher propensity to remain engaged in part-time work compared with non-tertiary women, highlighting how education may influence women’s likelihood of staying economically active while balancing family responsibilities. Part-time work enables women to manage care responsibilities such as childcare, and household duties but at the same time, it underscores the persistence of structural barriers that continue to hinder women from sustaining full-time participation in formal employment.

Figure 6: Respondents who has worked before but currently working part time with their educational attainment

Figure 7: Respondents who has worked before but has since stopped and their lastincome

Women’s decisions about work and family can be explained through how people choose to spend their time between paid and unpaid work. According to household production theory, many married women see household tasks such as childcare, eldercare, and managing the home as meaningful and productive work that directly benefits their families. In this view, time and effort are key resources used to produce what economists call “household commodities,” like the upbringing of children and family well-being. When the financial or emotional rewards from full- time jobs are too low, it can seem more worthwhile for women to focus on family responsibilities, where their contributions feel more valued.

Another way to understand women’s work choices is through the idea of “compensating differences.” Some women, especially mothers, may prefer jobs that offer flexibility, regular hours, or locations closer to home, even if these roles pay less or have limited career paths12. In this context, such “women-friendly” jobs trade higher earnings for the stability needed to balance work and caregiving13. However, when childcare, income support, and retirement systems are weak, stepping back from work can leave women more vulnerable over time. Women who leave or reduce paid work often lose access to benefits such as retirement savings, healthcare, and social protection. What seems like a practical choice in the short term can lead to long-term insecurity.

The economic rationale behind these choices is clear in the KRI-SRR survey findings. Among respondents who had previously worked, 41.9% earned below RM3,000 in their last job and 27% below RM1,500 (see Figure 7). In addition, our survey finds that 73.8% of those who had worked before transitioned from full-time employment to becoming housewives14. These figures suggest that many full-time jobs do not pay enough to offset the cost childcare, commuting, and managing family responsibilities.

Conclusions

In understanding women’s pathways in the labour force, particularly among those with tertiary education, the paradox of their participation cannot be separated from caregiving responsibilities and household dynamics. The findings reveal that higher educational attainment, often assumed to level the playing field for career advancement and labour market entry, does not necessarily translate into sustained participation. Instead, women’s entry, re-entry, or exit from the workforce is shaped by the intertwined pull and push of caregiving demands and economic considerations of employment renumeration which is level of pay, job security and accessibility of social services such as affordable care and family friendly support in workforce.

The common perception that educated women voluntarily opt out of work overlooks the structural and gendered barriers that limit their choices. Persistent inequalities in household roles and workplace expectations continue to position care as a women’s responsibility, reinforcing the divide between paid and unpaid work. For many women, unpaid caregiving is not a passive choice but a response to institutional and social constraints, while others navigate this tension through informal, self-employed, or gig work that offers flexibility but with risks that did not cover viable protection. Care must be recognised as a form of labour. Making unpaid care visible through better data and recognition is key. Frameworks like the 5R (Recognize, Reduce, Redistribute, Reward, and Represent) should translate into tangible policies that provide real protection and value15. The recognition means giving every caregiver a fair choice to care full- time or to work without paying the price socially or economically.