INTRODUCTION

The labour that goes into care work2 plays a pivotal role in enabling other forms of work to take place. Coupled with the growth of care migration3, where majority of the care migrants are women4, this has brought about two facets of labour—care and migration—that have important implications on gender.

Hence, the significance of linking care and migration on gender issues are undeniable and evident5. Economic development, urbanisation, and demographic changes add texture to the discourse, continuously shaping and moulding the dynamics between care, migration, and gender.

But policy thinking remains nascent6, with very little public discourse in Malaysia deliberating on the relationship between the two policy realms. With the increasing care burden in Malaysia, and the changing ways care services are provided to households, it is timely and opportune for policy makers to pay attention and deliberate.

Against this backdrop, this paper discusses the intersection of care and migration, and its implications for gender agenda in Malaysia, as encapsulated in the National Women Policy and the corresponding Action Plan for Women Development. The focus is on initiating the discourse and distilling policy considerations.

WOMEN’S LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION AND CARE

Women’s labour force participation sits at the core of Malaysia’s gender agenda, driven by both market forces and policy design.

The increasing costs of living, especially in larger urban centres, may have compelled some families to resort to becoming dual-career families7. This has contributed to the rise in women joining the workforce, breaching the 50% mark in 2013, after more than two decades of women’s labour force participation rate hovering in the 40-50% range, averaging 47.8% between 1995 and 2012 (see Figure 1).

The push for higher women’s labour force participation rate is given further impetus in official policy8. The 11th Malaysia Plan sets a target of 59% by the year 2020, from 54.1% at the end of the 10th Malaysia Plan period in 2015. While this is considerably modest when benchmarked against men’s labour force participation rate at 80.6% in 2015, it is perhaps a reflection of cautiousness on the part of policy makers, cognizant of persistent and emerging constraints preventing more women from entering the workforce.

One of the constraints is the rise in care needs9. Declining fertility rate and increasing life expectancy have resulted in a corresponding increase in old-age dependency ratio, defined as those aged 65 years and above as a share of those aged between 15 and 64 years. This has seen a spike from 6.4 in 2000 to 7.4 in 2010 and estimated to reach a high of 9.0 in 2017 (see Table 1).

.png)

Although youth dependency ratio—defined as those aged 14 years and below as a share of those aged between 15 and 64 years—has declined, the Child Care Centre (Institution Based) Regulations 2012 sets the minimum care provider-to-child ratio at 1:3 for children below the age of 1, 1:5 for children between 1 and 3 years old, and 1:10 for children aged between 3 and 4 years old. This means that the reduction in the number of children in a household, up to a large extent, does not change the number of care providers required for institutional care.

In fact, as expectation of childcare quality increases, there is an expectation that the ratio should be revised lower10, thus, together with the increasing demand for more institutional-based care, has put additional demand for care providers.

Against this backdrop, the question is obvious. Who would bear the increasing burden of care when more women enter the workforce, with men’s labour force participation remaining high? How can there be a convergence between men and women in their labour force participation rates if the care question is not resolved?

THE MIGRATION INTERSECTION

Given the above, foreign domestic workers provide an important option for families in navigating the demands of work and care. A focus on how families shift between a family-based care model that relies largely on family members—often women—and a migrant-in-the-family care model which employs home-based foreign domestic workers, illustrates the intertwined, but under-appreciated nature of the care discourse with migration.

The care-migration intersection has also received renewed attention in other countries, but with different permutations. The UK, Italy, Spain, Finland and France have seen a shift towards various forms of migrant-in-the-family care model e.g. the UK has an au pair programme and Spain combines subsidies for working mothers with quota allocations for foreign domestic workers11. This is necessitated by the retreat in the public provision of care services and incentivised by the introduction of cash provision and tax credit to assist families in purchasing care services from the market12. Consequently, the role of foreign domestic workers has oscillated between the migrant-in-the-family care model and migrant-in-the-market care model.

However, in the case of Malaysia, the migrant-in-the-family care model has emerged in the 1980s due to the lack of development of formal care provision—both public and private, and not because of the reversal in the public provision of care services. The first memorandum of understanding (MOU), known as the Medan Agreement, was signed with Indonesia in 1984 covering agriculture, plantation, and domestic workers13. In the same year, another MOU was signed with the Philippines focused on domestic workers14.

In 1999, post-Asian financial crisis, the government has put emphasis on diversifying the source countries for foreign workers15. Nonetheless, the three major countries that supply foreign domestic workers to Malaysia are still Indonesia, Philippines and Cambodia (see Figure 2).

.png)

STRAINS IN MALAYSIA’S CARE MIGRATION MODEL

Despite discernible improvements in Malaysia’s migration management system over the years and measures put in place by the government to ensure a steady supply of foreign domestic workers, the care migration sector remains small and accessible only to a small segment of the Malaysian households. A conservative estimate, if we assume that one household has one foreign domestic worker, put the number at 2% of total households that hire foreign domestic workers in 201616.

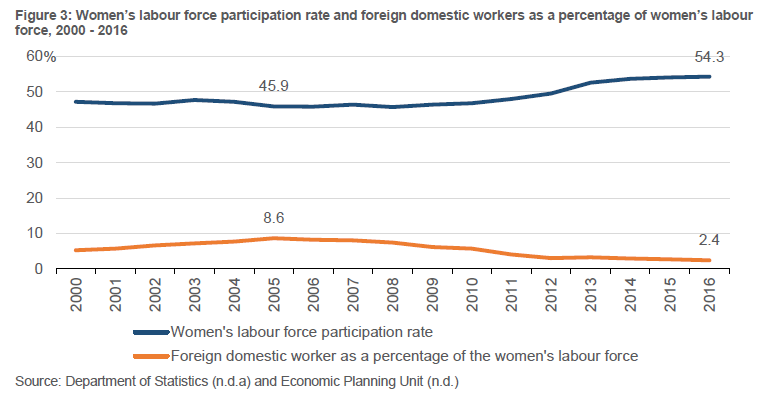

In fact, in the last decade or so, foreign domestic workers as a percentage of the women’s labour force has also declined from 8.6% in 2005 to 2.4% in 2016 (see Figure 3). This decline took place at the same time as the increase in the women’s labour force participation rate from 45.9% in 2005 to 54.3% in 2016. The rise in women joining the labour force without corresponding increase in the number of foreign domestic workers – instead, a reduction – reinforces the point that care migration has not been successfully posited as a viable, mainstream care option for families.

.png)

The decrease in foreign domestic workers is not just in percentage terms but also in absolute number. There has been a consistent decline in the number of foreign domestic workers since 2005, dropping to 134,575 persons in 2016, less than half of the foreign domestic workers employed at its peak at 320,171 persons (see Figure 4). This contrasts with the earlier period where the number of foreign domestic workers grew from 177,546 persons at the start of the millennium, amidst the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the dot-com bubble in 2001, to its peak in 2005.

.png)

The decline in foreign domestic workers, in absolute number and as a percentage of the women’s labour force, at the same time as the increase in the women’s labour force participation rate, posed a perplexing question for care. While the phenomena warrant a more detailed study—especially pertaining to how women manage the work-care space without relying on foreign domestic help—a few plausible reasons, at least on the demand side for households, can be offered to explain the decline.

One is the increasing cost of hiring a foreign domestic worker. In 2011, recruitment fees for Indonesian domestic workers was fixed at RM4,511, 60% to be borne by employers and a base wage at RM700 per month17. Prior to this protocol amendment to the MOU between Indonesia and Malaysia, the rates were even lower.

However, in recent years, agency fees could range from RM12,000 to RM18,00018. This is coupled with a monthly wage that could vary between RM700 and RM1,600 depending on individual agencies and the nationality of the worker19. The base wage for Indonesian domestic workers is RM900 and there was a proposal by the Indonesian embassy in 2015 to increase this to RM1,20020.

Taking the median points of RM15,000 for hiring costs and RM1,150 for the monthly wage, this gives a monthly cost of RM1,775 over a 24-month contractual period, not inclusive of accommodation and other living expenses (see Table 2).

Given a median household income of RM5,228 in 201621, this means that the monthly cost of having a foreign domestic worker would constitute 34.0% of median household income. The situation is even more acute for the bottom 40% income group (B40), defined as households earning below RM4,360 in 2016, where the monthly cost would constitute 40.7% of household income, and would, by definition, worsen as the household income goes lower.

.png)

Furthermore, the eligibility criterion that a prospective employer must earn a net income of RM3,000 or RM5,000 per month, depending on the nationality of the foreign domestic worker, has already precluded a large percentage of B40 households from accessing foreign domestic help to meet their care needs. This is compounded by another eligibility criterion that the employer must be married – precluding unmarried individuals with genuine care needs22.

The high cost incurred, and the risk associated with it when foreign domestic workers abscond, are borne disproportionately by individual employers. To mitigate the risk, many employers resort to soliciting the help of family members to ‘supervise’ the foreign domestic workers. The difficulties involved in mobilising the help of family members to either directly provide care or to supervise the foreign care worker, add to the strain in the current care migration model.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FAMILIES

The challenges associated with the hiring of foreign domestic workers, preventing the scaling up of the care migration sector, coincide with the limited public provision of care services and the relatively undeveloped private care market23.

In 2014, the enrolment of children aged 0 to 4 in childcare centres registered with the Department of Social Welfare (DSW) constitutes only 2.41% of the total children in the same age group, increasing marginally to 2.93% in 201624. This could be partly due to the cost factor as well. According to our findings from Choong et al. (2018), the basic fees for childcare within Kuala Lumpur and Selangor can range fairly widely from less than RM100 to above RM900 monthly, with most centres quoting the fees in the RM300 to RM500 range (Figure 5). Similarly, elderly care costs range between RM900 and RM5000 per month. Whilst these costs are on average lower than the costs of hiring a foreign domestic worker, the total cost burden depends on the number of dependents a household needs to support financially25,26.

.png)

As a result, these may shape new forms of family arrangements to cope with the increasing care needs. An immediate family member—often women—may not enter or drop out of the labour force when the reconciliation of paid work and the care burden becomes impossible27. In 2017, 59.5% or 2.8 million women cited housework as the reason for not joining the workforce, compared to only 3.1% or 69,800 men.

Alternatively, women may take on less demanding—plus lower paying—jobs to have the flexibility to manage both care and work. The advantage of flexibility, however, comes with vulnerability and precarity of working conditions28. The statistics in Malaysia is telling. Between 2010 and 2017, one third of the increase in women’s labour force participation is explained by the rise in own account workers i.e. independent or self-employed workers. Its growth of 26.4%, from 2.1 million to 2.6 million, outpaced all other forms of employment.

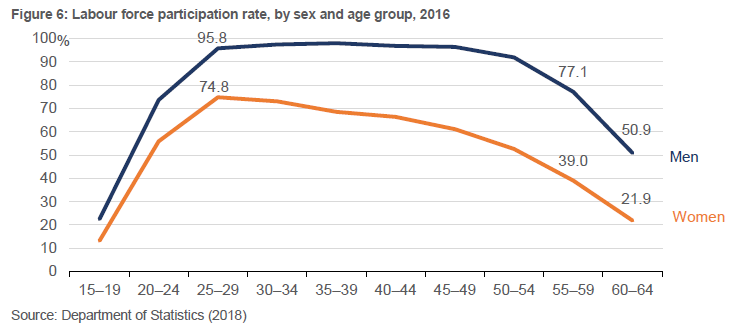

The dual-worker families would also seek the help of extended family members, especially those in the late 50s or early 60s29, who may have to balance between providing childcare (for their grandchildren) and elderly care (for their elderly parents). This means that women of these age groups would have to drop out of the workforce to enable the younger women to participate, thus offsetting any increase in the women’s labour force participation of the younger age groups.

In Malaysia, women’s labour force participation rate culminates at the age groups of 25 and 29 years before decreasing. The women’s labour force participation rates for those in the age groups of 55 and 59 years, and 60 and 64 years, are at 39.0% and 21.9% respectively in 2017, less than half of the men’s labour participation rates for the same age groups (see Figure 6). While more needs to be done to understand the numbers, it offers a hypothesis that younger, dual-worker families in Malaysia may seek the assistance of women in the late 50s and early 60s to navigate the work-care space when hiring foreign domestic workers is either not feasible or unaffordable.

NEGOTIATING MIGRATION AND CARE POLICIES

Acknowledging the high cost of hiring foreign domestic workers, the government announced during the tabling of the 2018 budget that the hiring cost will be reviewed with the goal of reducing it and would allow the direct hiring of foreign domestic workers beginning from January 1st, 2018, through an online platform facilitated by the Immigration Department of Malaysia30.

Notwithstanding legitimate operational and diplomatic concerns raised with regards to this new policy31, direct recruitment would effectively reduce hiring cost by a substantial amount, signalling government’s intention to increase the affordability of hiring foreign domestic workers. The migration policy reinforces a combination of migrant-in-the-family and family-based care model.

On care, however, the broad policy, as stated in the 11th Malaysia Plan, is headed in the direction of promoting the development of a formal care sector, predominantly in partnership with the private sector and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)/community-based organizations (CBOs). On the other hand, public provision of care services remains small, designed for, and targeted at welfare purposes.

To enhance the role of women in development and raise women’s labour force participation rate, emphasis is put on the expansion and accessibility of quality childcare services, in partnership with private sector and NGOs/CBOs, supported by a gamut of employment-related measures such as flexible working hours, work-from-home options, and employment re-entry opportunities. Similarly, various measures have been announced to improve elderly care services and establish elderly day care centres in partnership with NGOs with the aim of enabling family members to work.

The simultaneous promulgation of two care models—migrant-in-the-family/family-based care model and formal care sector/family-friendly working arrangements—although not necessarily contradictory, highlights the importance of synchronizing migration policies and care policies in supporting women’s labour force participation32.

A proper assessment of the labour supply and demand for the formal care sector may reveal potential labour shortage that can be filled by foreign workers, which can then be supported by a carefully-targeted migration policy that does not focus only on mobilising home-based foreign domestic help. A migration policy that spreads out the risks and costs of foreign domestic worker absconding may also reduce the reliance on family members—often women—for help, thus bolstering women’s labour force participation by reducing dropouts.

CONCLUDING POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

While not taking a conclusive position on either model, there are discernible benefits for Malaysia to develop an alternative care model centred on the formal provision of care supported by employment-related measures. It provides choice for families seeking care options and creates job opportunities.

Concerns over the affordability of private sector-driven formal care services can be balanced with the enhancement of public provision of care services and community-based care arrangements. In addition, measures can be taken to allow the hiring of foreign workers in the formal care sector as a cost reduction strategy, albeit with important trade-off on the salaries and well-being of care providers.

Both care models raise different gender questions—the migrant-in-the-family/family-based care model reinforces the role of women in domestic work and may require a different group of women to take up care work in enabling other women to enter the workforce.

The formal care sector/family-friendly working arrangements would create job opportunities for local and foreign women, raising new gender questions on working conditions and new care gaps, particularly for foreign women workers who leave their children and family members behind to provide care in another country33.

By assessing the contradictions and complementarity of these models, as well as the intersection of care and migration policies, the trade-offs between gender equity and quality of care provision, affordability of care and the quality of care-givers, can be drawn out for further policy deliberations and discourse.

Only by having a clear and comprehensive care strategy, underpinned by a supportive migration regime, can the women’s labour force participation rate be meaningfully increased.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not necessarily represent the official views of Khazanah Research Institute.

.avif)