Why first- and last-mile access matters

Greater Kuala Lumpur (GKL)’s rail network, particularly the MRT and LRT, provides very frequent and reliable services. For the record, MRTs and certain LRT lines have headways of 3-4 minutes during peak hours, which is on par with global standards. Yet, for many commuters, the decision to use public transport is not determined by the quality of service of the train itself, but by the experience of getting to and from it.

These first- and last-mile journeys often require navigating a series of small but consequential friction points. Commuters face uneven pavements, unsafe road crossings, long walking distances, or the need to arrange informal alternatives at short notice.

Individually, these frictions appear minor. Collectively, they shape whether public transport is perceived as usable on a daily basis. When the effort, risk, or uncertainty involved in reaching a station exceeds a commuter’s tolerance threshold, the rational response is to default to private vehicles, even when rail systems are frequent and reliable.

Qualitative interviews from our discussion paper1 illustrate how these frictions compound. Respondents frequently described feeling exhausted from making trips. At times, they are uncertain about whether they could complete the return journey reliably. Importantly, first- and last- mile failures are not solely an infrastructure problem. They reflect a mismatch between how the transport system is designed and how commuters actually make decisions. Where access requires excessive walking, unsafe crossings, or unreliable transfers, commuters are forced to absorb risk and effort upfront. Over time, this erodes commuter confidence and reduces willingness to use public transport, even among those who recognise its advantages.

First-and-Last Mile Gaps in practice

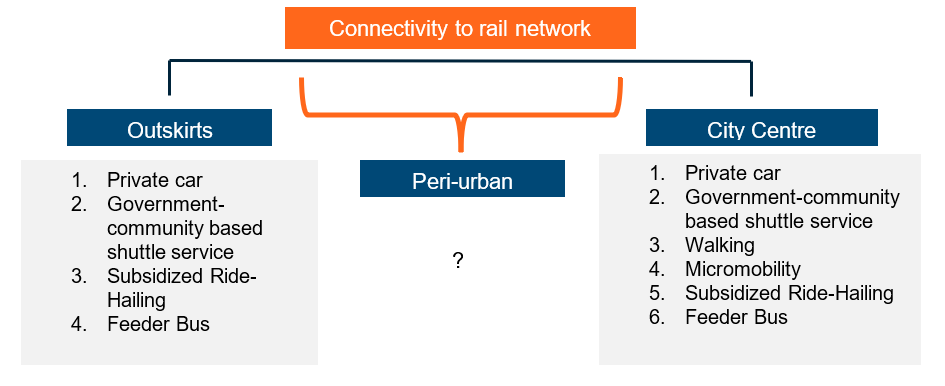

Access to rail stations differ markedly between urban and sub-urban2 settings. In central areas, commuters are often surrounded by multiple transport nodes, giving them flexibility to connect to the rail network. By contrast, those living in sub-urban or peri-urban areas frequently rely on a single access option, making their journeys more vulnerable to disruption.

As one respondent noted:

“I still have to drive or ride a bike to the station.” (R6)

Another explained:

“But if you’re in the sub-urban areas, like the outskirts, the connectivity is not reliable and not so convenient.” (R33)

In many outlying areas, houses is more dispersed, with a higher prevalence of landed properties. Walking distances to stations are often too long, leaving commuters dependent on driving. Even in central areas, proximity does not immediately guarantee accessibility. Stations such as Salak Selatan are physically severed from surrounding neighbourhoods by highways and major roads, limiting walkability despite geographical proximity.

Walking as a source of effort and risk

Where walking is required, the journey to the station is frequently uncomfortable and unsafe. Respondents described broken pavements, poor lighting, lack of shelter and exposure to traffic as recurring challenges.

One commuter explained:

“The walkway is not very pleasant to walk on, because you have all these pavements that’s broken, you have tree roots coming up, you don’t have shades.” (R4)

“The pedestrian walkway is covered, but it’s got no lighting. So the moment it rains or it comes towards the evening, it’s very dark and dodgy.” (R4)

Another highlighted inconsistent walking conditions:

“Tapi kalau hujan tu kena basah, dia tak ada cover walkway. Dia punya sidewalk… mula-mula dia batu-batu, lepas tu dia jadi tanah. Dia rumput yang kena pijak – bukan official walkway.” (R17)

At night, these risks intensify. Several respondents described routes that felt deserted or dangerous after dark:

“Walking to the station is quite secluded and dark at night. There’s no proper lighting or continued pathway.” (R24)

One respondent recounted having to walk directly on the roadside and using a phone flashlight to signal her presence to passing vehicles:

“There is no pavement so I’m literally walking on the side of the road. Because the path is quite dark at night, so I remember having to use my phone’s flashlight, not just to see where I was going, but to make sure cars could see me and wouldn’t hit me.” (R1)

These accounts show that walking is not a neutral activity. It involves making ongoing judgements about safety, comfort, and sometimes navigating poor visibility conditions, particularly for early morning and late-night trips.

Coping mechanisms and system responses

Where first- and last-mile access is weak, commuters adopt coping mechanisms. Outlying settlements become increasingly reliant on private vehicles to reach stations, prompting the demand for large park-and-ride facilities. Demand-responsive transit (DRT) schemes have been introduced in some areas, but their coverage and reliability is yet to be ascertained.

These responses alleviate access constraints in the short-term, but they really are symptomatic of deeper integration gaps that require a longer-term solution. They shift costs onto operators and commuters while reinforcing car dependence around stations.

What the evidence suggests

Taken together these differences reveal that first- and last-mile barriers operate as a cumulative burden. Long distances, unsafe walking environments, and the need to improvise alternatives raise the effort, risk, and uncertainty associated with making the first- or last-mile trip. Over time, this burden shapes commuter behaviour, determining whether public transport remains a sustainable daily choice.

Crucially, the nature of this burden differs by spatial context. In dense urban areas, walkability, safety and continuity of pedestrian infrastructure are the binding constraints. In peri-urban and sub-urban areas, distance and coordination dominate. In lower-density clusters, conventional feeder models would struggle to deliver reliable access.

Figure 1 summarises how connectivity options to the rail network differ between city centres, peri-urban areas, and the outskirts in GKL.

Figure 1: First-and-last mile connectivity strategies in Greater Kuala Lumpur.

This policy brief argues that closing the first- and last- mile gap is therefore essential to unlocking the full value of Greater KL’s public transport network. Addressing these gaps requires targeted, context specific interventions that reduce effort, improve safety and lower uncertainty across different urban settings.

Policy Recommendations: Closing the First-and-Last-Mile Gap Through Context Specific Interventions

Improving first- and last-mile access in Greater KL requires recognizing that commuters face different constraints depending on where they live. Different neighbourhoods present distinct challenges, and no single intervention is sufficient across all contexts. The following recommendations outline complementary strategies matched to those differing conditions:

Urban cores: make walking safe, continuous, and predictable

In dense urban areas where walking to rail stations is feasible, policy efforts should prioritize improving pedestrian conditions along key access routes. Many commuters already live within nominal walking distance of stations, but broken pavements, inadequate lighting, unsafe crossings, and exposure to heat and rain raise the effort and perceived risk of walking. Addressing these barriers through continuous and well-maintained pavements, adequate lighting, and passive surveillance, safer road crossings, and sheltered walkways that are regularly maintained can substantially improve access and walkability. Small, targeted improvements along frequently used routes can have outsized effects. When walking becomes safe, predictable, and comfortable, commuters are more willing to rely on rail services consistently.

Peri-Urban Areas: reduce the impact of distance and coordination burdens

In peri-urban and suburban settings, distances to stations are often too long for walking, and feeder services tend to be less frequent or reliable. In these contexts, first-mile interventions should focus on reducing coordination burdens. Integrated or subsidised ride-hailing services for first-mile trips and micromobility options where road conditions permit can provide flexible alternatives that narrow the gap and improve reliability. These approaches allow commuters to reach stations without the need to drive and park one’s car at the station. In Finland, several pilot projects have been conducted in collaboration with their ministry of transport, including the ongoing Whim service which offers monthly packages of public transport, taxis and car rentals3. This initiative works successfully in developing a cost-efficient transport sector in Finland.

Low-Density Clusters: deploy targeted community-scale services

In low-density areas, conventional fixed-route feeder services are often inefficient and difficult to sustain. DRT or community-scale shuttle services can play a role when deployed selectively, particularly when they are focused on specific neighbourhoods or communities, aligned with peak travel periods and evaluated based on reliability rather than coverage. Where access gaps remain, park-and-ride facilities would continue to be in demand for the short term. However, these should be treated as interim coping mechanisms rather than permanent solutions, as they shift costs onto commuters, while reinforcing car dependency around stations.

Conclusion: A system-wide principle – reduce effort, risk, and uncertainty

Across all spatial contexts, effective first- and last-mile interventions share a common objective: reducing the effort, risk and uncertainty commuters face before and after using public transport. Success should not be measured solely by physical proximity or infrastructure provision, but by whether access conditions make public transport easier to sustain as a daily habit. By aligning interventions with the lived realities of different neighbourhoods, policymakers can improve access without resorting to one-size-fits-all solutions and ensure that existing rail investments deliver their intended benefits

Greater KL has already invested heavily in rail infrastructure. Whether these investments translate into sustained public transport use depends on what happens before and after the train ride itself. For many commuters, the first- and last-mile conditions determine whether public transport is viable as a daily choice.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).avif)