Introduction

Was this article AI-generated, or did a human write it?1

The ability to generate convincing text, audio, images and video using simple prompts has been hailed by some as progress towards “democratisation of content creation”2. However, this powerful capability also comes with negative impacts. Within two years of mass access to generative AI (or gen-AI), the integrity of our information, communication and media landscape has been thrown into question.

Much attention has been focused on malicious use, such as deepfakes in electoral disinformation campaigns or non-consensual pornographic images. However, a much less discussed topic is the unintended consequences of the ability to mass produce content cheaply, thoughtlessly and at times erroneously.

This is the first of a three-part series on “AI slop”, referring to an overload of low-quality AI-generated content. In Part 1, we introduce the term and offer examples of areas that have been inundated by such content and discuss the drivers behind its proliferation. Parts 2 and 3 cover the consequences of AI slop from the perspectives of content consumers and content creators, society at large, and the AI models themselves

What is AI Slop?

The term “AI slop” has entered modern lexicon, referring to low quality content (usually text, audio, images and video) generated by AI that is convincing at first glance but reveals its lack of substance upon deeper engagement. One dictionary definition of “slop” is “food waste (such as garbage) fed to animals”3, providing vivid imagery of the nature of content that is being consumed.

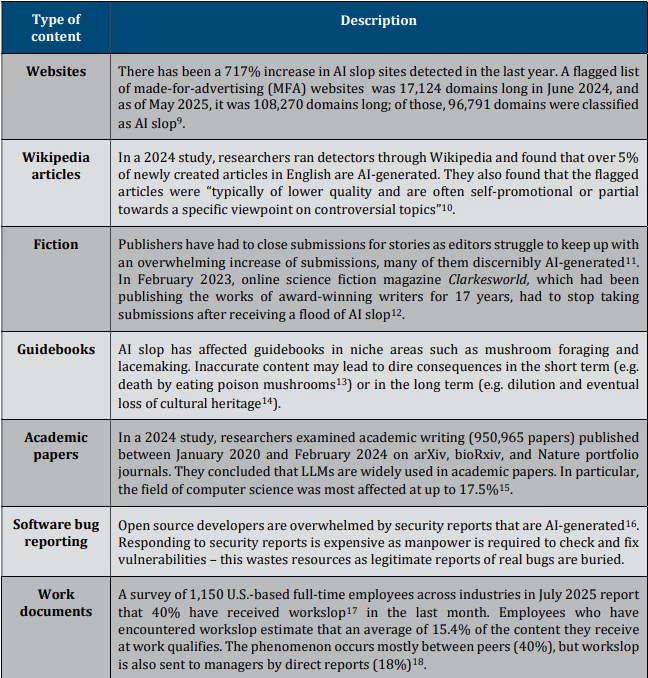

Experts have differentiated AI slop from disinformation, and instead call it “careless speech” or even “bullshit”, where inaccuracies and biases are subtle and not overtly wrong. This happens because the main goal of the generated content is not to be accurate or inaccurate, but to be persuasive4. For instance, Large Language Models (LLMs) are perfectly suited for generating convincing text as they can be prompted to generate any form or style of speech (see Table 1 for a non-exhaustive list of examples of niches that have been affected).

Other gen-AI models on video, images, and audio have also achieved the level of quality that they can be mistaken for human-made content. In recent weeks5, readers may have noticed an onslaught of AI-generated videos in their social media feeds, due to new video apps launched by OpenAI, Meta and Google, to name a few. In particular, Sora 2 by OpenAI has grabbed headlines and caused multiple controversies, due to the social nature of the app whereby users can use likenesses of themselves and others to generate convincing deepfake videos6.

For music, accounts pumping out AI-generated music are reaching massive audiences. In June 2025, a fake rock band called the Velvet Sundown amassed more than 1 million Spotify plays in weeks7. Spotify has also revealed that it removed 75 million spam tracks from its platform over the past year as AI tools increase the ability of fraudsters to create fake music to generate income from streaming. The scale of the problem is significant, as Spotify’s actual catalogue stands at 100 million tracks8

Table 1. Examples of AI slop in text form

The increasing accessibility of tools to generate AI slop is worrying, especially in engaging forms such as video. The concerns boil down to the questionable quality and authenticity of AI-generated content and the crowding out of genuine humanmade content that takes time, energy and expertise to produce.

Mechanisms for quality assurance, traditionally human editors and curators, cannot match the volume or speed of AI content that are generated in seconds with simple prompts. Even large platforms such as Amazon have had to set publication limits – in Amazon’s case, to no more than three books per author per day19. This is not a high threshold, considering the amount of effort conventionally required to produce a full-length book.

Beyond practical considerations, there is also a moral dimension. Gen-AI relies on training data that often includes copyrighted material or scraped web content without permission of the original creators to use their work to train AI20, not to mention compensation. Content creators therefore receive a double whammy of being exploited and being crowded out of the market.

Profiling from AI Slop

Why is there so much sloppy content?

There is a clear financial incentive for those creating content cheaply and monetising it. There are relatively straightforward ways to do this, such as hawking AI-generated e-books on Amazon directly to consumers. However, some have taken more sophisticated measures.

One example that has gained notoriety is the “SEO Heist” by a tech entrepreneur named Jake Ward (see Figure 1), who boasted on social media about stealing traffic from a rival website with the help of AI. As spelt out by Ward, his agency copied the structure of a popular website Exceljet21 and populated the skeleton with 1,800 pages of AI-generated content in a manner of hours. Using search engine optimisation, or SEO22, he claimed to have diverted 3.6million views from Exceljet to his own website within the span of 18 months23.

Figure 1. SEO Heist

Another example covered by Wired tells the story of a man who bought defunct news websites (such as Hong Kong’s Apple Daily) and filled them up with AI-generated clickbait content, profiting from the websites’ strong search engine rankings from their popularity in the past24. Observers are sounding alarms at the ease in which these operations are carried out25, as top search results become dominated by AI-generated content26.

Platforms to the rescue?

In an environment of content overload, the role of platforms as curators and moderators increases in importance. Much of our content and media now reside on large online platforms or rely on them as gatekeepers – they therefore become the de facto arbiters of what is considered appropriate and acceptable for consumption for large populations of users across the world.

Could we rely on them to separate signal from noise in our online environment?

Early signs are mixed. On one hand, large platforms, like small-time profiteers mentioned above, are also subject to the profit motive behind AI-generated content. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta has made it clear that Meta’s platforms Facebook and Instagram will embrace AI-generated content in their newsfeeds, adding “a whole new category of content which is AI-generated or AI-summarized content, or existing content pulled together by AI in some way”27. The release of Vibes, Meta AI’s new video feed, is an implementation of this vision, algorithmically personalising the AI-generated videos to individual users to maximise engagement28.

On the other hand, content platforms also recognise that the proliferation of AI-generated content may drive away users looking for authenticity. For example, Spotify’s rival streaming platform Deezer announced that it would label AI-generated tracks and ensure that their reach would be limited in both handpicked and algorithmic playlists29.

Conclusion

With the amount of AI-generated content flooding all aspects of communication, it is increasingly difficult to separate signal from noise. While some have lauded the earning potential and productivity gains of generative AI, we will also need to be clear-eyed about unintended and longer term consequences.

The proliferation of AI-generated content has the potential to overwhelm the area of information, communication and media. The content is often generated with a short-term profit motive, with the overload drowning out quality content and information. What is at stake? A healthy information ecosystem supports informed citizens in their participation in democracy, and authentic human expression is the bedrock of culture and social connection.

We explore some of these concerns in the next article in the series.

.avif)