This View is Part 2 of a three-part analysis of the US-Malaysia trade deal. Part 1 looked at the new tariffs and industrial policy, while Part 3 looks at the interaction between foreign policy and industrial policy.

A New Type of Trade Deal

While the bulk of the 482-page Agreement Between the United States of America and Malaysia on Reciprocal Tariffs 2025 (USMART[1])covers tariffs, the final agreement extends beyond tariffs to cover areas of economic and foreign policy. There are significant implications of the USMART on Malaysia’s economy, industrial policy, and foreign policy. This paper offers a non-comprehensive initial assessment of these key issues.

Out of the post-Liberation Day trade deals struck by Trump, only the Malaysian and Cambodian (USCART) deals have been published in full. These deals have enough similarities to suggest that they were derived from a new template that is more extensive and detailed than the US-UK Economic Prosperity Deal and US-EU Framework on an Agreement on Reciprocal, Fair, and Balanced Trade previously announced in May and July 2025, respectively.

The USMART and USCART are also less detailed than past US FTAs. They nonetheless contain binding obligations. In terms of the non-tariff topics covered, they include what the US identifies as non-tariff barriers such as standards, services, intellectual property, taxes, digital trade, state-owned enterprises, as well as a host of prescriptive policy demands covering labour rights and – surprisingly for the anti-green stance taken by Trump – demands for trade partners to meet high environmental standards (albeit, not climate).

These topics are familiar ground covered in US FTAs since the early 2000s. FTAs struck under former president George W. Bush focused on making economic deals with close US security partners such as Jordan, Oman, Singapore and South Korea, building upon the first FTA signed by the US with Israel in 1985. The USMART and USCART offer an evolution of these FTAs offered to US security partners by now including provisions for “economic and security alignment” with countries generally considered to be neutral.

Novel Legality

The legal basis of these new deals is also novel. Trump’s so-called “reciprocal tariffs” are not empowered by Congressional trade authority. Rather they derive from presidential executive orders based on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which gives the president powers during war or emergency. Trump is the first president to use IEEPA to tackle tariffs[2].

These orders were ruled illegal in May 2025 by the US Court of International Trade, although subsequently the appeals court stayed the ruling[3]. Trump’s use of IEEPA is currently being challenged in the US Supreme Court[4]. If the Court finds against Trump then the USMART and similar deals could be rendered void.

There are signs that the Trump administration is preparing a contingency plan if its novel use of IEEPA is overturned. This could potentially rely on Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, which supports measures allegedly based on national security. However, on 29September, the White House imposed Section 232 tariffs on imports of timber and lumber, upholstered wooden products and kitchen cabinets and vanities.

While the US Navy uses wood in ships for certain purposes, it is hard to accept at face value national security claims regarding wood products unless the US military wishes to revisit the glory days of the English victory at Agincourt through the mass adoption of longbows, let alone vanities and kitchen cabinets. It is more reasonable to conclude that Section232 tariffs on wood seek to pander to vested interests.

USMART and the WTO

The USMART contains multiple references to the WTO, sixteen in total, including both Parties’ “rights and obligations” under the WTO agreements and requiring Malaysia to back certain policies at the WTO. This sits uncomfortably with several facts.

The first being that the Trump tariffs violate the principle of Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) provided for under Article I of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) 1994, which prohibits discrimination among members of the WTO. Furthermore, Article II of the GATT binds tariffs within rates listed in the schedules. The 25% or 19% Trump tariffs violate this since they are applied on top of the MFN rate and effectively create a hierarchy of favoured and unfavoured nations[5].

Second, the US has for years now blocked the full functioning of the dispute settlement mechanism at the WTO by refusing to support the appointment of judges to the WTO’s Appellate Body, meaning that cases cannot be resolved. This was to protect the US from being found at fault in numerous cases filed against it.

Thus, while the USMART makes much reference to WTO legality, it also undermines it. The US’ ambiguous positioning against the WTO was further complicated as on 29 October, 2025, the day after the USMART was signed, the US quietly paid its overdue fees to the WTO.

This suggests that the Trump administration still sees some use in the WTO despite the US’ unilateral trade measures. Potentially, the use of reciprocal tariff agreements to lock partner countries into backing specific positions at the WTO would help make the multilateral body more compliant to US interests.

Key Provisions

Taking a closer look at the USMART beyond tariffs, its demands on standards, services, intellectual property, taxes, digital trade, state-owned enterprises, labour and the environment are largely not new in intent. They will be familiar to those who tracked US demands when it was part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The general intent of such non-trade measures is to restrict the policy space of developing countries to pursue industrial policies and priorities that could result in divergent standards and practices from those in the US. While developing countries are generally willing to learn how to conform to the standards of developed countries in order to secure market access for their exports, developed countries may prefer to use their power to circumvent such a learning process for their firms.

The more countries the US gets to agree to such terms, the more universal US standards, policies and practices become. Given the structural inequalities and self-admitted deficiencies of the US economy, this may prove to be unsuitable to the long-term development of other countries who may have different ideas on standards of food safety, social redistribution, monopoly power, environmental quality, labour rights and the appropriate role of private enterprises, especially the ability of very large corporations to shape regulatory standards and extend their ownership and control of the economy.

Malaysian consumers of food, digital services and pharmaceuticals will now have to pay close attention to regulatory developments in Washington as the USMART will transmit these standards to Malaysia. Malaysia’s regulatory practice until now is that domestic authorities maintain the right to have a different view of standards following a rigorous and legitimate process. If the Malaysian government is unable to affect regulations of US origin in favour of the Malaysian consumer then consumers may have to become more educated and aware about the health and social implications of US regulatory decisions.

Sections 5 and 6 of the USMART present some novel developments and challenges for Malaysia’s industrial policy. Section 5covers Economic and National Security. Section 6 covers Commercial Considerations and Opportunities, particularly issues of investment and state-owned enterprises.

Economic and Security Alignment

Recent US trade deals with Europe and Southeast Asian countries contain provisions for economic and security alignment on export controls and activities of third country companies. The provisions affecting Malaysia are part of an emerging international legal architecture being established by the US beyond its traditional circle of allies.

Article 5.1 – Economic and Security Alignment

Article 5.1 Complementary Actions focuses on “economic and security alignment” between the US and Malaysia. This takes three forms.

First, in 5.1.1 an obligation on Malaysia to replicate “a customs duty, quota, prohibition, fee, charge, or other import restriction on a good or service” imposed by the US on a third country that represents a “shared economic or national security concern”. This appears to be a strong obligation on Malaysia to follow US policy with respect to certain countries[6].

A potentially critical term here is “shared”, which has been the subject of speculation. In order to not comply with 5.1.1 the burden would be on Malaysia to show to the US that it does not share economic or national security concerns with respect to a third country.

Otherwise, there appears to be little to no discretion for Malaysia to opt out of such alignment except to delay implementation. Should Malaysia point out that it does not share the US’ economic or security concerns, then the US could attempt to make the case for shared concerns – perhaps referring back to records taken during negotiation of the USMART or the bilateral memorandum of understanding on defence cooperation signed in the week after the ASEAN Summit[7], failing which in the last instance, it could threaten to revoke the USMART per Article 7.

Given that the USMART has no provisions for dispute resolution the ball is largely in the US’ court. While both parties can terminate the USMART, doing so would reimpose the 25% tariff earlier placed on Malaysia under IEEPA Executive Order 14257.

The equivalent provision in the USCART does not give Cambodia discretion to opt out, only that it shall implement such measures “in a manner that does not infringe on Cambodia’s sovereign interests.” If the US imposes a measure on, say, China, then Cambodia would be obliged to impose a similar measure. How it does so without infringing on its sovereign interests will have to be determined by Cambodia. Logically, it does not preclude Cambodia from being caught in a double bind.

Second, in 5.1.2 are measures that oblige Malaysia, in accordance with its domestic laws and regulations, to act on the companies of third countries operating in Malaysia that the US deems to be engaging in unfair practices that result in:

(a) the export of below-market price goods to the United States;

(b) increased exports of such goods to the United States;

(c) a reduction in U.S. exports to Malaysia; or

(d) a reduction in U.S. exports to third-country markets.

On the one hand, 5.1.2 serves to ensure that third countries do not take advantage of the Malaysian tariff rates secured under the USMART. Third country companies could do so via transshipment or by setting up operations in Malaysia that import largely finished goods from a third country for final export to the US. Such practices have been ongoing for years in Malaysia. The US Department of Commerce has in the past imposed antidumping and countervailing duties on foreign companies in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia’s solar photovoltaic manufacturing sector[8].

5.1.2 may have the effect of reducing FDI from third countries intent on transshipment or low-value added manufacturing. This could be to Malaysia’s long-term benefit since Malaysia has struggled to turn away low quality FDI in its desire to meet quantitative investment targets. However, for the restriction to be truly beneficial, Malaysia would need to have industrial policy measures that genuinely promote spillovers such as technology transfers from FDI.

Malaysia is forbidden from imposing technology transfer as a condition for doing business. Under Article 3.4 of the USMART, “Malaysia shall not impose any condition or enforce any undertaking requiring U.S. persons to transfer or provide access to a particular technology, production process, source code, or other proprietary knowledge, or to purchase, utilize, or accord a preference toa particular technology, as a condition for doing business in its territory.”

Exemptions are provided for the cases of source code provision, software for critical infrastructure, government procurement, and financial prudential reasons.

This is perhaps not as limiting for industrial policy as it appears at face value. While it is desirable for host governments to ensure that technology transfer balances the value extracted by multinational corporations (MNCs), successful transfer does not need to take the form of an entry condition. Therefore, other approaches to technology transfer could be strengthened, such as joint ventures, supply chain upgrading, research and development collaborations with public institutions, skilled local hiring policies, and the like.

Is it possible that Article 5.1.2 may not be mandatory for Malaysia given that the obligation should be “in accordance with its domestic laws and regulations”? The implication of this argument is that present Malaysian laws may not cover restrictive measures on third countries, therefore no action can be taken to fulfil Malaysia’s obligation. However, the obligation “shall” comes prior and implies that Malaysia should fulfil the obligation via national legal and regulatory powers. The absence of any enabling laws and regulations does not preclude such policies being created.

The equivalent provision in the USCART is worded differently:

At the request of the United States, Cambodia shall, consistent with its sovereign interests, adopt and implement measures to address unfair practices of companies owned or controlled by third countries operating in Cambodia’s jurisdiction.

At first reading, this would seem to imply that Cambodia’s binding obligation to the US should be mitigated by its “sovereign interests” however those may be defined. However, similar to Article5.1.1 Cambodia is not accorded discretion. The phrasing is not ‘Cambodia shall, IF consistent with its sovereign interests, adopt and implement measures…’.Rather, the obligation the obligation to adopt and implement measures is primary. Making them consistent with its sovereign interests is a task for the Cambodian authorities to figure out. This burden is however contingent upon the US making requests for action. Malaysia’s commitment has no such conditionality and takes effect from the entry of the USMART into force.

For both Malaysia and Cambodia, the key question is whether the US is willing to tolerate non-compliance with 5.1.2. Actual or apparent flexibility in wording is less material than the discretionary ability of the US to withdraw privileges.

For Malaysia, the most practically problematic subclause in 5.1.2 is (d), tackling a third country company whose exports from Malaysia lead to “a reduction in U.S. exports to third-country markets”. This is asking Malaysia to take responsibility for the economic goings on and consumer choices in a third country, which is well beyond the ability of most countries unless they are able to sign an economic agreement that alters the policy environment in a third country.

Consider a hypothetical example. The EU favours its multinational companies through a variety of funds, grants and subsidies. EU MNCs can channel FDI to Malaysia in order to seek lower costs of production for export back to the EU market. The US competes with EU companies in the European market. If the US determines that European subsidies to their MNCs in Malaysia are a source of unfair competition that reduce US exports to Europes, then Malaysia would be obliged to take action against EU MNCs. The US and the EU have a long history of WTO disputes over their respective subsidies deployed for their MNCs.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement

A final complication posed by Article 5.1.2 is its interaction with existing economic treaties between Malaysia and third countries.

Policing third country companies could lead Malaysia to be targeted by trade reprisals from third countries. This could be via WTO or non-WTO measures. The WTO has a dispute settlement process, but it lacks a final court of appeal due to US interference. Cases can end in administrative limbo – an “appeal into the void”. To that end, a subset of 29 countries at the WTO have formed the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) to resolve disputes among themselves. In 2025, Malaysia joined the MPIA which includes countries such as Australia, China, Canada, the EU (27 members), Hong Kong-China, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore, and Switzerland. MPIA members could in theory contest actions taken under Article 5.1.2 of the USMART.

In terms of non-WTO measures, this could potentially leave Malaysia open to retaliatory Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) actions from investors of third countries – suits by companies lodged in private arbitration courts outside Malaysian jurisdiction. ISDS suits can amount to billions of dollars. Malaysia has more than 70 international investment agreements, including the CPTPP and the ASEAN-China Investment Agreement (2009). The ASEAN+5 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) does not presently include ISDS, but its inclusion is being debated.

Similar challenges may lie ahead for other ASEAN countries signing Reciprocal Tariff agreements with the US.

Article 5.1.3 - Shipbuilding

Article 5.1.3 has amore explicit wording of how Malaysia is expected to meet its obligations to the US via its domestic regulatory process.

Malaysia shall adopt, through its domestic regulatory process, similar measures of equivalent restrictive effect as those adopted by the United States to encourage shipbuilding and shipping by market economy countries.

The US shipbuilding industry has declined since the Second World War and the security implications of China’s swift rise in commercial shipping production has alarmed the past two administrations in Washington[9].Reforms of US cabotage policy, known colloquially as the Jones Act, may now boost opportunities for allied economies such as South Korea and Japan to provide manufacture, and maintenance, repair and overhaul services for US ships.

Trump’s executive order of 9 April, 2025mentions engaging allies and partners to impose actions on Chinese shipbuilding dominance. It is unclear whether USMART Article 5.1.3 envisions this type of action.

Article 5.2 – Economic Containment Measures

Article 5.2 Export Controls, Sanctions, Investment Security, and Related Matters, obliges Malaysia, through its domestic regulatory process, to cooperate with the US “to regulate the trade in national security-sensitive technologies and goods” and “align with all unilateral export controls in force by the United States”.

Malaysia has existing cooperation on export controls with the US under the Strategic Trade Act 2010, which attempts to restrict the use of Malaysia as a transshipment hub. This has recently extended to advanced artificial intelligence (AI) chips, such as those brokered via Singapore[10].

Article 5.2.3 obliges Malaysia to explore establishing national security screening for inbound investment. This includes critical minerals and critical infrastructure and to cooperate with the US on matters of investment security. Article 5.2.4 appears to offer a carrot that suggests that if Malaysia cooperates the US could show some accommodation in its investment security measures. While vague, this could imply revisiting the export of edge computing and sophisticated AI chips to Malaysia imposed under the Biden administration.

Article 5.3 Other Measures contains a provision under 5.3.3 restricting Malaysia’s freedom to enter trade and economic agreements with countries the US deems a jeopardy:

If Malaysia enters into a new bilateral free trade agreement or preferential economic agreement with a country that jeopardizes essential U.S. interests, the United States may, if consultations with Malaysia fail to resolve its concerns, terminate this Agreement and reimpose the applicable reciprocal tariff rate set forth in Executive Order 14257 of April 2, 2025.

The wording stipulates “bilateral” as opposed to multilateral or plurilateral. So in theory the upgraded ASEAN-China trade agreement signed immediately after the USMART is potentially neither “new” nor bilateral. While cooperation with BRICS countries is usually at the level of memoranda of understanding, Article 5.3.3 may overshadow any future desire to sign a trade deal with the likes of Russia should that align with Malaysia’s strategic interests. This provision thus cedes policy space in both trade and foreign policy.

Article 5.3.4 restricts purchases of nuclear-related materials from undefined “certain countries, except where there are no alternative suppliers on comparable terms and conditions.” This is primarily a geopolitical rather than commercial provision, underlining that nuclear capability is still of concern in superpower rivalry.

Commercial Considerations and Opportunities

Article 6.1 – Investment

Article 6.1.1 obliges Malaysia to “facilitate and promote investment by the United States in sectors including critical minerals, energy resources, power generation, telecommunications, transportation, and infrastructure services”. However, Malaysia already does so via its national investment agency and an investment regime liberalised following decades of FTA concessions. The issueis more whether US corporations in those sectors are willing to invest.

However, the US may be seeking to ensure that it is not explicity frozen out of those sectors in the future. This does give an explicit list of what sectors are of interest to or a source of anxiety for the current US administration, however this may be subject to change in the future.

Weaker language in Article 6.1.2 offers consideration of investment in Malaysia from the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM Bank) and International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). EXIM Bank is a recently revived government-linked corporation (GLC) in the US. From2015 until May 2025, it had lacked sufficient board members to back investments greater than USD10 million[11].However, in August it approved more than USD100 million in financing guarantees for data centres and digitalisation in Cote d’Ivoire[12].

DFC is a relatively new development finance institution that has undergone a tumultuous period of reauthorisation[13]. However, it appears to be an international development institution that the Trump administration wishes to keep in play to support US national and private sector interests abroad.

Eyebrows may be raised in mainstream Malaysia at Article 6.1.3’s obligation that “Malaysia shall facilitate, to the extent practicable, approximatelyUSD70 billion in job-creating investment, including greenfield investment, in the United States over the next 10 years.”

This appears to reverse the common belief that it is developed countries that should invest in developing countries. Trump seems to share the belief that compelling investment into the US suffices as an industrial policy. Developing countries do invest in developed countries, albeit primarily financial investments, since returns often tend to be greater than those in emerging markets.

Investing USD70billion into greenfield investments in the US could be an opportunity to extract wealth from the US, just as western multinationals have extracted wealth from developing countries for decades.

The US offers generous tax exemptions and access to industrial subsidies at state and federal levels (especially if investors are willing to invest in lobbying efforts). Offshoring profits back to Malaysia, directly or via a third country, can increase the returns for Malaysian investment in the US. This can be used to strengthen productive capabilities back in Malaysia, including for export to non-US markets.

If Malaysian investors are not interested in technology transfer they can either conduct low technology activities or engage in technology licensing to increase payments from their US subsidiary to the Malaysian parent. If US labour is too expensive, emphasis can be placed on highly automated activities to reduce the jobs footprint.

While this involves more risk due to capital outlays, access to US subsidies can transfer risk to the host government. While there are genuine bureaucratic, skilled labour and supply chain challenges to establishing a business in the US – due to a decades-long decline in manufacturing – the regulatory system is highly skewed in favour of private enterprise over social or environmental interests.

For example, the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation, a state-owned sovereign wealth fund known as GIC – chaired by former Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong – owns over half a million acres of forest land in Michigan[14]. Its main activities are logging. This may prove a way to circumvent and even benefit from Section 232 tariffs on wood products being imported into the US. Since Singapore is too small to sustain a domestic logging industry, it can make money overseas by logging American trees, shielded behind protective tariffs. The profits can be repatriated to Singapore.

The Trump administration is focused on flows of goods rather than flows of finance, so financial outflows from Singaporean investments can help evade challenges in the current policy environment. There are potentially valuable lessons here for Malaysian private capital to study and understand.

Article 6.2 – Commercial Considerations for State-Owned Enterprises

Article 6.2 on Commercial Considerations presents more of a challenge to Malaysia’s domestic industrial policy as it concerns State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), or GLCs. 6.2 requires Malaysia to ensure that when SOEs engage in commercial activities they:

“(a) act in accordance with commercial considerations in their purchase or sale of goods or services; and

“(b) refrain from discriminating against U.S. goods or services.

“Malaysia shall refrain from providing non-commercial assistance or otherwise subsidizing its goods-producing SOEs, except for the achievement of their public service obligations. Malaysia shall ensure a level playing field for U.S. companies in Malaysia’s market with respect to SOEs of third countries.”

The terms and provisions of this article are broad and lack definition. Does it include all SOEs at both state and federal level? Does it extend to include PETRONAS and what Malaysia calls Government-Linked Investment Companies (GLICs) such as Khazanah Nasional, Permodalan Nasional Berhad and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (LTAT), or the Employees Provident Fund (EPF)?

SOEs are often used by all kinds of countries to achieve developmental objectives that are not necessarily oriented towards short-term profit. Article 6.2, requires that when engaging in “commercial activities”, SOEs should “act in accordance with commercial considerations in their purchase or sale of goods or services”. Crucially, this is a provision with universal applicability beyond just relations with the US. However, it does not prohibit SOEs from undertaking non-commercial activities that are not profitable. In the absence of a clear distinction between commercial and non-commercial activities Malaysia may have some leeway. Article 6.2 is notably less detailed than Chapter 17 of the CPTPP on SOEs and Designated Monopolies.

6.2(a) effectively targets procurement which is a powerful tool to ensure commercial support for local companies that the government wishes to achieve scale. Support at the national level can help them compete in international markets. Similar “infant industry” policies were used by developed countries to build them to their present day strength. Via the WTO and plurilateral and regional FTAs, developed countries have sought for decades to “kick away the ladder” and restrict the ability of developing countries to pursue similar policies.

Taken together with6.2(b), these provisions aim to give US multinational companies comparable access to local procurement as enjoyed by other firms. Large companies may be able to undercut competitors in order to secure contracts.

This does not rule out favoured procurement for local firms, but it does mean that government will have to get creative if it wants to support local businesses in procurement. Policies could be deployed to support suppliers rather than via clients. Alternatively, SOEs can designate certain operations to be not profit maximising as part of an obligation to support national development objectives.

The obligation to refrain from subsidising good-producing SOEs, except for the achievement of their public service obligations, is also unclear. On the one hand, it narrows such subsidies to public service obligations. On the other hand, it is unclear what those may be. Can Malaysia freely define these?

For example, TNB’s provision of electricity is subsidised by the government, is this a violation of USMART? Likewise, PETRONAS’ sale of petrol is subsidised by the government, is it also a violation of the USMART? Both subsidies are intended to lower the cost of living of Malaysians, and to some extent non-Malaysians, operating in Malaysia. Does this qualify as a public service obligation?

Ensuring a level-playing field for US companies with respect to third country companies is likely a reference to the regulatory principle of competitive neutrality which will be addressed in a separate Views. Suffice to say that taking on responsibilities for third countries complicates regulatory compliance for Malaysian authorities and is likely to require increases in capacity and capabilities.

Article 6.3 - Purchases

Article 6.3 outlines intended purchases by Malaysian companies of goods from the US, detailed in Annex IV. This is of interest to the US in order to narrow its trade deficit with Malaysia. This implies an increase of imports from the US and a corresponding narrowing of Malaysia’s current account surplus.

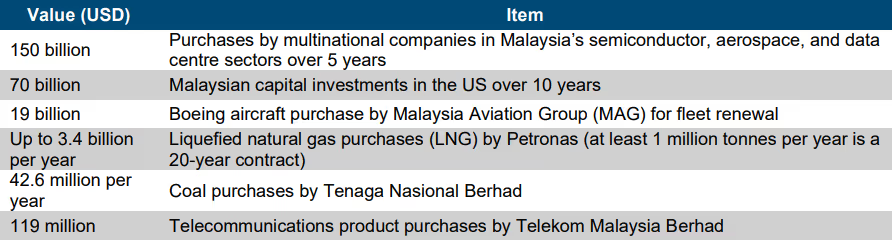

According to a Parliamentary statement by the Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry total investment and purchase commitments amounted to over RM1 trillion (USD 240billion, Table 1)[15].

The exercise of collecting and packaging existing and planned purchases was a relatively shrewd way to present a more complete picture of bilateral trade to the US. This may have spared Malaysia from making higher commitments. South Korea, for example, has pledged to invest USD350 billion in the US[16]. Japan, meanwhile, has pledged USD550 billion in the US, and the EU has agreed to purchase USD750billion in US energy and make new investments of USD600 billion in the US, all by 2028[17].

It is unclear whether the purchases by Malaysian SOEs were made based on commercial considerations asper Article 6.2 of the USMART or whether they were driven by other considerations.

Table 1: US Purchase and Investment Commitments by Malaysia

While Article 6.3 specifies purchases by Malaysian companies of US goods, the Parliamentary statement and Appendix 1 of the USMART appear suggest that planned purchases by US MNCs operating in Malaysia are considered acceptable. For national accounting, such as the balance of payments or current account surplus, capital purchases by foreign affiliates of MNCs do accrue as imports by the host country.

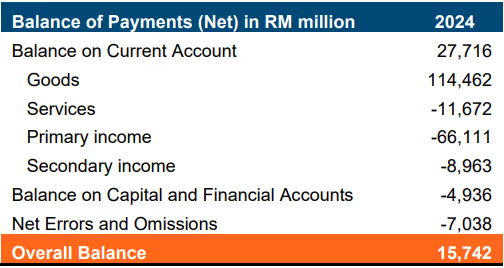

Table 2: Malaysia, Balance of Payments, 2024

Malaysia’s current account surplus was around USD6.6 billion (RM27.7 billion) in 2024 (Table 2). TheUSD150 billion of purchases over five years by MNCs and potential annual LNG purchases alone would drive the current account into a deficit of almost USD27billion (RM111.6 billion) per year from the 2024 baseline.

A persistent current account deficit can sometimes be sustainable. But in the presence of a budget deficit it could lead to a twin deficit, which could lead to rising interest rates, increased foreign ownership of domestic assets, exchange rate instability, and a challenge for the government to balance the current account, either with a heroic expansion of exports or a reduction in imports, or an increase in borrowing.

The capital investment in the semiconductor sector that makes up over two thirds of the USD150 billion will presumably lead to an eventual boost in exports. Otherwise, import substitution industrialisation has traditionally been used in Malaysia over the decades to boost local industries and reduce external dependence. Combined with export-focused efforts this could help redress the trade balance in the long-term.

Malaysia’s investments in the US could potentially help offset a current account deficit by repatriating profits and increasing Malaysia’s dollar earnings.

On the plus side, without the consultations involved in the USMART process the Malaysian government may have gone unaware that impending purchases by MNCs were threatening a current account deficit. Note, according to official sources these purchases would have taken place regardless of the USMART.

The last time Malaysia ran a sustained current account deficit was in the 1990s prior to the Asian Financial Crisis. The deficit reached a peak of 10.2% of Gross National Income(GNI) in 1995. The “deficit was primarily attributed to escalated imports of intermediate goods, notably for the electrical and electronics (E&E)industries, which heavily relied on imported raw materials sourced from Taiwan, Japan, and the United States”[18].It is notable that the single largest forward purchase item in Table 1 is for semiconductor materials, which at an estimated USD103 billion account for 42.9% of total pledged purchases under the USMART.

Malaysian negotiators may not have realised the financial risks associated with the large purchases from the US. The oncoming parallels with the 1990s may have also escaped policymakers working on Malaysia’s current National Semiconductor Strategy(NSS).

The South Korean negotiations with the US have notably voiced concern over the risk of financial crisis similar to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis in light of the US demand for them to invest USD350 billion. South Korea’s foreign exchange reserves amount to USD410 billion, the Korean won is not staple global currency, thus a lumpsum transfer of USD350 billion would induce a currency shock. They tried to negotiate for a currency swap line between the Bank of Korea and the Federal Reserve. Eventually, agreement appears to have been reached on a two-tier format: i)USD200 billion would be invested in the US at a rate capped at USD20 billion per year; and, ii) USD150 billion would be invested in a bilateral shipbuilding partnership[19]. By capping their direct investment commitment annually South Korea secured some stability and predictability.

With the US pushing partner countries for similar purchase commitments, developing country partners could be unduly exposed to financial crisis. One of the future consequences of the present trade shakeup could be multiple national financial crises, possibly combining into regional or global crises, due to massive financial transfers into the US. This would depress demand for US goods and potentially interrupt inward investment transfers. The Trump agenda could unwind from its own actions.

Annex III Specific Commitments

Annex III of the USMART includes detailed specific commitments by Malaysia that broadly oblige it to accept and adopt US standards and regulatory practices. A full analysis of the implications of the 14-page annex is beyond the scope of this paper and requires separate treatment. However, in relation to industrial policy a brief comment is merited on Annex III’s Article 6.2 on critical minerals.

6.2.1 states that Malaysia “shall refrain from banning critical mineral exports to the United States and shall eliminate any rare earth element export quotas to the United States.” However, Malaysia has subsequently stated that it intends to continue its policy restricting the exports of raw unprocessed rare earths in order to support downstream expansion[20].

This would seem like a violation of the deal, but in practical terms, US capabilities to process rare earths to a finished state are effectively non-existent. Importing raw rare earths would do them no good. Annex III Article 6.2.2 and 6.2.3 commit Malaysia to developing its critical minerals sector together with the US, including guarantees against restriction on exports of rare earth magnets used in industrial applications. There are similarities to Article 6.1 in the main agreement with the US not wanting to be frozen out of specific sectors. US has signed complementary critical mineral MOUs with Australia, Japan, and Thailand.

US Vulnerabilities Targeted By New Deals

The US interest in diversifying supply partners and guarantees of no export bans is due to its dependence on China for rare earth products. Due to its global dominance in rare earth manufacturing China was able to restrict supply to the US to become the only country in the world capable to negotiating a suspension of the Trump tariffs. This is a demonstrable benefit of a successful industrial policy.

The ability of developed countries to coerce China has been limited by China’s ability to choke off global supply chains that it dominates, as well as its realisation that doing so yields negotiating results.

During the first Trump presidency, Beijing attempted a non-confrontational approach, but that only resulted in more punitive tariffs. By the second Trump presidency, China has adapted with targeted retaliatory measures that have so far proved successful in taming US economic coercion.

Most developing countries, Malaysia included, lack the industrial policy success to pull off a similar negotiation tactic. They remain dependent on advanced countries’ manufacturing firms for industrial strength.

Prior to the 1970s,the international production of oil was dominated by Western multinational corporations, the “seven sisters”: BP, Chevron, Esso (Exxon), Gulf Oil, Mobil, Shell, Texaco. In the 1970s, the strength of developing countries in oil production and supply allowed the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to impose an embargo on the US and other allies of Israel during the Fourth Arab-Israeli War that began on 6 October, 1973. This coordinated action induced the first oil shock and caused oil prices to quadruple within three months, leading to fuel shortages and a prolonged economic crisis in the US and elsewhere[21].

The US today, has insulated itself from this vulnerability via industrial policy measures focused on becoming the world’s top oil and gas producer, and – less successfully – renewable energy. In fact, in 1973 Exxon pioneered the commercial sale of solar photovoltaic panels.

One of the lessons Malaysia can take from this is that while the relative failure of past industrial policies did not leave it with a strong negotiating position for the USMART, it can seek to develop this kind of national and economic security potential in the future. Having pledged access to its critical minerals, this may point to the need to explore other sectors in which to achieve leverage.

We should note that industrial success is not enough in itself. Japan and South Korea are standout examples of industrialisation. However, they remain dependent on the US in terms of exports and national security. The South Korean deal is yet to be concluded, but reports suggest that they have been able to reduce their Trump tariff rate from 25% to 15%, as well as secure a 15% rate for critical auto exports which normally fall under Section 232. South Korea had previously sacrificed considerable policy space to the US when they signed the 2007 Korea-USFTA (KORUS). The bilateral FTA did not prevent Trump tariffs from being imposed on them. Thus, US trading partners should never forget that the rule of law can be trumped by the rule of strength.

Conclusion

There are many long-term industrial policy implications stemming from the USMART. The preceding analysis only touches upon a selection of articles which have significant industrial or macroeconomic implications. The USMART was negotiated under short-term pressure. If the government did not have time to sufficiently take account of the long-term and structural implications there is still a window of opportunity to address them.

Pursuant to Article7.2 of the USMART, the agreement will only enter into force 60 days after an exchange of notifications following the completion of legal procedures. The signing at the ASEAN Summit was merely a step along the way to full legalratification. There is thus an indeterminate amount of time between now and the finalisation of legal procedures.

Trade deals are negotiated in secret, and the USMART is no exception. The public and stakeholders do not get to view the entirety of a trade deal until after the negotiating parties have themselves reached agreement. The only time for public review and discussion of the USMART is now, during this period of legal limbo. The government has an opportunity to take in views from a broad range of stakeholders during this period.

Preparing for the implementation of Articles 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3 may require new domestic laws and regulations. For example, what is the current legal basis for Malaysia to discipline a third country company for transshipment? To date, punitive measures by the US Department of Commerce have been a strong driver of stopping transshipment of solar panels via tariffs as high as 3,521% for companies in Cambodia[22]. Action by Malaysia against third country companies could invite legal reprisals, including ISDS challenges.

If legal reforms need to go through Parliament this gives a broad window for Malaysian concerns to be raised with the US and the government. Alternatively, if domestic processes take time they can also take account of the impending decision of the US Supreme Court which could void the President’s IEEPA tariff authority.

This could invalidate the tariffs presented in the USMART and push the White House to find an alternative legislative or executive basis for its tariff agenda, such as Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act. The tariff authority of Donald Trump is one built on shifting legal sands. Malaysia should proceed cautiously in this desert of geopolitics. These issues are explored further in Part 3.

.avif)