Promoting growth to combat global inequality

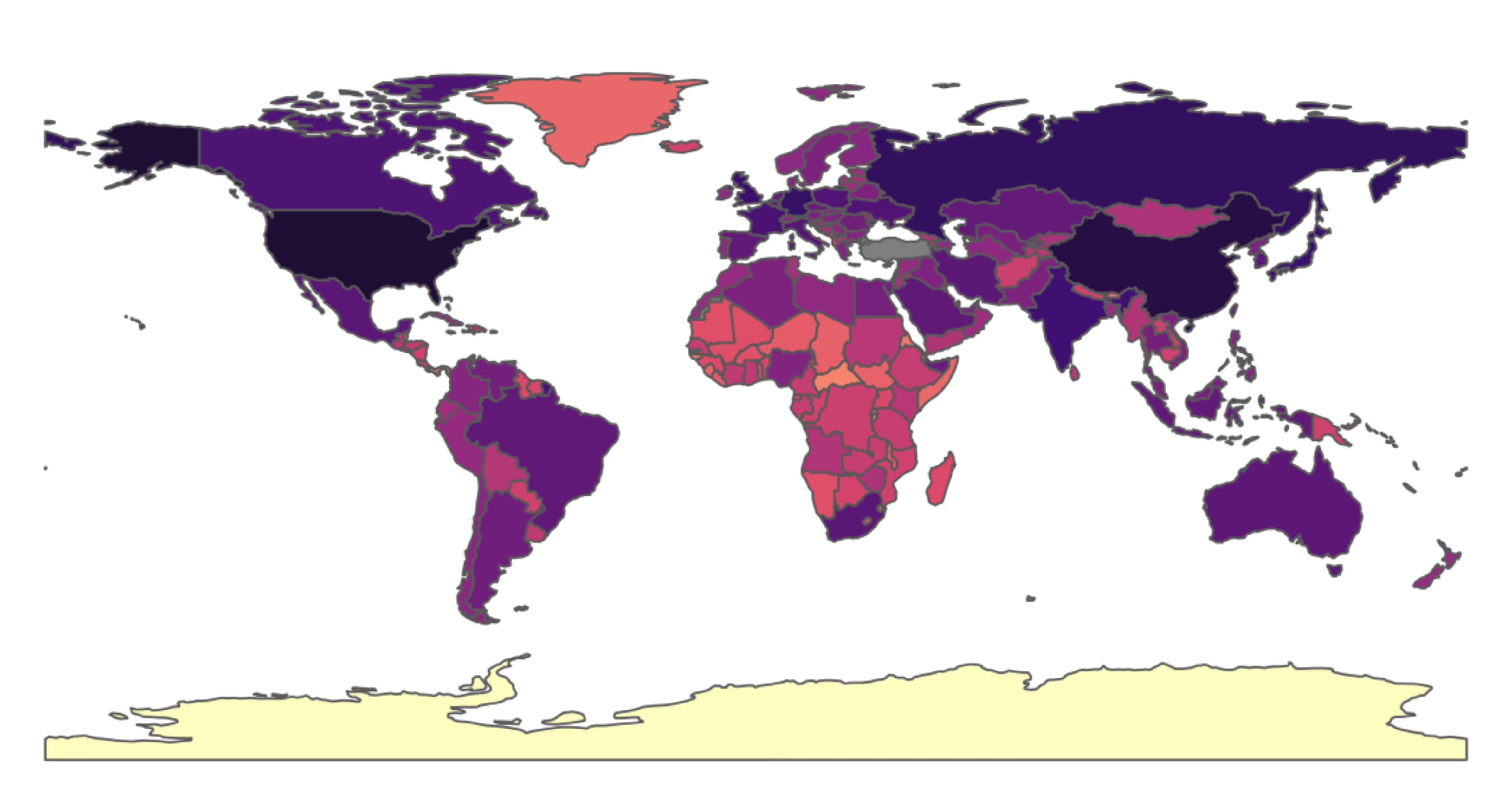

One of the novelties in the recent pivot towards "global inequality" as an empirical and normative project is the use of "individuals" as the main unit of analysis, as though "they were living within one nation" (Christiansen and Jensen 2019). It marks a departure from assessing global disparities with average gross domestic product (GDP) per capita across countries, or what is also known in the literature as "international inequality" (Christiansen and Jensen 2019). Contrary to the earlier period before World War II where global inequality was on the rise (Bourguignon and Morrisson 2002), more recent estimates show that global inequality has been trending downwards, with a shift towards between-country inequality as the paramount contributor, underpinned by the rapid economic growth of China (Lakner and Milanovic 2013; Milanovic 2020). This has perhaps given impetus to the view that promoting economic growth is a powerful way of combating global inequality.

The role of economic growth in the long-term reduction of inequality has its roots in the seminal paper titled "Economic Growth and Income Inequality" written by the economist Simon Kuznets in the 1950s (Kuznets 1955). Although Kuznets' analysis was based on an extremely small sample of industrialised countries, it led to the popular conceptualisation of an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and inequality-also called the Kuznets curve. At its core is the argument that structural transformation, which accompanies economic growth, would drive up inequality in the early phase of industrialisation, but as more workers move from agriculture to industries, equalising effects would set in and reduce overall inequality. Applying Kuznets to the discourse on global inequality, Milanovic (2016, 50-59) extends Kuznets' original formulation to what he called the Kuznets waves, an alternating pattern of increasing and decreasing inequalities that comes with long-term economic growth, supplying evidence to the premise that economic growth is still a major driving force for global inequality reduction.

There are empirical and normative issues with the global inequality project. On the empirical side, adjusting for standard errors or top income presents an ambiguous trend of global inequality (Lakner and Milanovic 2013), thus compelling a rethinking of the evidence. On the normative side, objections may be raised as to whether methodological nationalism (Christiansen and Jensen 2019) is being replaced here by a form of methodological individualism, detracting from group-based or categorical inequalities that may be more pertinent; or over the fact that global inequality reduction could be merely statistical if it could be brought down by events that wreaked havoc on people's livelihoods, such as a financial crisis (Milanovic 2020). Nonetheless, even if we accept the premise that growth is pivotal for inequality reduction, I argue that more emphasis should be given to the quality of growth and the role of power. At the same time, the ongoing discourse on degrowth poses a new normative challenge to the growth premise. In the fiercely debated topic on the role of (de)growth in reducing global inequality, Malaysia should perhaps think ahead in terms of balancing its ambitions of attaining high income and its commitment to larger socio-ecological goals.

Complexities of structural change and deindustrialisation

The underlying economic structure that informs Kuznets is markedly different from the more complexed and varied ones we have today. The Kuznetsian economic worldview is basically dualistic in that structural change is conceived of as a transition from a relatively low productivity agriculture sector to high productivity industries-or primarily manufacturing. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that such conceptualisation of the economy, and its attendant structural change processes, may be too simplistic for the contemporary global economy. The dualistic assumption is problematic for two reasons: first, even non-agriculture sectors-both industries and services-can be separated into high and low productivity sub-sectors; and second, there are multiple pathways to achieve structural change beyond the linear agriculture-to-manufacturing transition (Baymul and Sen 2020). Therefore, the presence of low productivity manufacturing and services sub-sectors suggests that the processes underlying economic growth are not always characterised by a "low-to-high" productivity pathway but also "low-to-low" productivity structural change. Baymul and Sen 2020 shows that there are contrasting inequality dynamics generated for countries with different economic structures and undergoing different pathways of structural transformation. While the Kuznets postulate still stands to some extent, particularly for services-driven structural transformation (Baymul and Sen 2020), it provokes the question of whether there should be a distinction between high quality (low-to-high productivity) and low quality (low-to-low productivity) economic growth.

Unlike the Global North, low quality economic growth prevails in the Global South, often associated with premature deindustrialisation¹. Premature deindustrialisation is the economic transition to-often low productivity-services without sufficient development of the manufacturing base of the economy, spawning a range of political and economic implications for the countries involved (Rodrik 2016). Although the rise of China, arguably a developing country, is attributed to be the most crucial factor in the reduction of global inequality (Lakner and Milanovic 2013; Milanovic 2016), it is hardly convincing to think that the sui generis growth of China, with its commanding population, can be replicated elsewhere. In fact, the onset of deindustrialisation in Southeast Asia has coincided with China's admission to the World Trade Organization (Asyraf, Shamri, and Sivabalan 2019; Lee and Choong 2019; Mohammad Zulfan Tadjoeddin 2019; Tuaño and Cruz 2019), suggesting trade-offs within the Global South itself. In Malaysia, while inequality reduction has occurred alongside economic growth, the underlying trend of deindustrialisation hints at a convergence towards broad-based low value-added activities² instead of being driven by a more dynamic catching up process (Khazanah Research Institute 2020a; 2020b). All these point to an economic growth prescription that needs to be more discriminate in terms of quality, and not just quantity, in combating global inequality.

Navigating between-country and within-country dynamics

In economic parlance, economic growth generates factor income that can be broken down into capital income, labour income and net factor income from abroad. On the other hand, global inequality is calculated based on a mix of household income³ and consumption using the Gini coefficient (Lakner and Milanovic 2013). Hence, the transmission of factor income to household income (or consumption) encapsulates the processes that link economic growth to global inequality. Beyond macroeconomic considerations, the magnitude of factor income that can be transmitted to households depends on the power relations between different economic actors in these intermediating processes at both the global and national levels.

Fundamentally, there is the power relations between foreign capital and state actors. Given the proliferation of supply chains spread around the globe, centred on large multinational companies predominantly located in the Global North, the capacity of state actors in the Global South to minimise surplus extraction is a key determinant of global inequality reduction. Surplus extraction that are repatriated back to the centre of production affects the ability of Global South countries, at the sites of production, to capture a larger share of economic growth for its national economic actors, including households. This relationship of surplus extraction has echoes of past colonialism (Habib 1975; Piketty 2020) but more contemporary expressions with ideological and state backing are perhaps most actively advocated in the form of neoliberalism (Hickel 2017).

Therefore, international political mobilisation needs to focus on empowering state actors in the Global South to retain factor income from economic production and secure the policy space to determine how economic surplus should be distributed. Having said that, nested within this is the equally important power relations between state actors and the country's population. Even if factor income is retained in developing countries, state capture and other forms of destructive rent-seeking (Khan and Jomo 2000) may inhibit a more equitable distribution of economic surplus to the people. For example, this can be in the form of low and unfair wages paid to workers or tax revenue used for private gains instead of public goods. Conversely, widespread discontent with within-country inequality could have played a role in the populist backlash seen in the Global North, and when perceived as linked to the global inequality project e.g., the rise of China (Rodrik 2019), would further derail efforts to improve people's welfare based on between-country convergence (Milanovic and Roemer 2016). In sum, economic growth will not trickle down to improve global inequality, but political actions at both the global and national levels are critical in safeguarding a socially just distribution of the benefits of growth.

The normative challenge of degrowth

At first glance, there does not seem to be a contradiction between degrowth and the economic growth needed to reduce global inequality. After all, "proponents of degrowth are clear that it is specifically high-income countries that need to degrow" (Hickel 2020). This means that the economic growth of the Global South, which has led to the current decrease in global inequality, is consistent with the degrowth paradigm. However, on closer reading, there are deeper critiques of degrowth that may pose a normative challenge to the economic growth envisioned in the global inequality project.

As highlighted earlier, the empirical basis on which economic growth is envisioned to bring about a reduction in global inequality is largely drawn from the growth experience of China, and if extended, also large populous countries like India and Indonesia (Lakner and Milanovic 2013). But can this kind of growth trajectories and levels be sustained without exceeding our planetary boundaries or natural limits (Raworth 2017; Hickel 2020)? Even Branko Milanovic, a leading economist in the field of inequality and a strident critique of degrowth, admits that it would require a trebling of GDP if everyone in the world is to catch up to the median income of the Global North, and that is before factoring in population growth (Milanovic 2018). To evoke the analogy, "A rising tide might not lift all boats... Instead, it might simply flood us all out of existence" (Abrahamian 2018). Therefore, even if proponents of economic growth do not accept the degrowth solutions, the ecological concerns of degrowth underscores a significant challenge to the kind of populous, environmentally damaging growth that has driven down global inequality in the past few decades.

The ecological argument is underpinned by the call for a different way of organising global production, one that is driven less by the logic of unrestrained market capitalism and excessive consumption (Hickel 2020), but one that respects ecological limits and enhances social foundations such as education, healthcare and housing (Raworth 2017). More fundamentally, degrowth problematises the current economic growth path as rooted in a form of neo-colonial and exploitative dependency that has kept the Global South in low productivity economic activities coupled with unfair terms of trade (Hickel 2017; 2020). While this is not to say that there are no problems with the degrowth paradigm-such as the interchangeable reference of GDP and material throughput; abstract suggestions for the Global South to get out of dependency; and insufficient attention to the processes of capital accumulation (Foster 2011)-it ultimately suggests that neither economic growth nor global inequality is a valid normative goal. Instead, degrowth puts forward an alternative normative project of building a new kind of human and ecologically centred society, grounded in a new and fairer set of global economic relationships (Hickel 2020).

Concluding reflections for Malaysia

The view that economic growth is a powerful way of combating global inequality can be situated in a kind of pragmatic empiricism informed by the rise of China or the economic growth of any large populous country. This argument has its theoretical roots in the work of Kuznets and updated more recently by Milanovic (2016) in the form of the Kuznets waves, where the pre-Industrial Revolution period was included. Against this backdrop, even if we accept the premise that economic growth is an effective tool to steer global inequality reduction, it is the quality not just the quantity of economic growth that would ensure global inequality reduction is welfare enhancing. It is perhaps worth reiterating that economic growth does not trickle down and hence political actions that navigate between-country and within-country power dynamics are crucial in safeguarding an equitable distribution of the benefits of economic growth. On the other hand, degrowth poses a powerful normative challenge to the entire premise that economic growth is good for global inequality reduction, centring ecological concerns and calling for a new logic of organising production-this places both economic growth and global inequality on the periphery of the agenda.

Amid post-pandemic realities coupled with renewed zeal for climate agendas, the debate on the role of growth vs degrowth in the global development discourse would likely become more vigorous, contested and polarising moving forward-with implications for global supply chains in which Malaysia is deeply embedded. As a small, open economy with industrial and technological ambitions of catching up with the Global North, Malaysia has to pay attention to this emerging debate as it strategically positions itself in this fast changing landscape, while charting the 12th Malaysia Plan and the next phase of its industrial policy. Malaysia's development trajectory has to be buttressed not only by high productivity economic growth in order to achieve convergence with the Global North, but also sustain a growth project that translates into decent jobs, reduces inequality and upholds ecological commitments on the global stage. How well Malaysia balances these diverse and sometimes competing goals depends on its ability to navigate power at the global level, and manage power relations within its own national borders.